|

| The Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, which today is part of the Hermitage Museum (Wikimedia Commons) |

Delicate, ornate works made in the workshop of Fabergé are among the most sought-after art objects in the world—which means that there’s also a healthy market for Fabergé fakes. Questions over the authenticity of some Fabergé pieces have come to light recently in Russia, in a growing scandal involving a famous museum, an oligarch, and a skeptical art dealer.

|

| The Hermitage Museum (Wikimedia Commons) |

The Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, the second-largest art museum in the world, is currently featuring an exhibition of Fabergé pieces. The Fabergé collection owned by the Hermitage is relatively small, so most of the items on display are loans from other institutions. These include a private Fabergé museum owned by wealthy Russian businessman Alexander Ivanov. He established the museum in Baden-Baden, Germany, in 2009 to hold his personal Fabergé collection. Ivanov told the press eleven years ago that the collection was worth something in the neighborhood of $2 billion.

Ivanov, a major collector and broker of Fabergé pieces, came to prominence more than a decade ago when he purchased the Rothschild Fabergé Egg at Christie’s in London. The egg, made for Edouard and Germaine de Rothschild in 1902, was sold at auction in November 2007. Ivanov paid more than $12 million USD for the item (and later was pursued by the British government over VAT payment issues).

|

| The Rothschild Fabergé Egg is displayed at Christie’s in London ahead of its auction, October 2007 (SHAUN CURRY/AFP via Getty Images) |

The Rothschild egg may have been many people’s introduction to Ivanov, but he didn’t keep the egg in his personal collection after the sale. Instead, he donated it to the Russian government in 2014. Vladimir Putin subsequently presented the egg to the Hermitage Museum in December 2014, as part of the museum’s 250th anniversary celebrations.

Ivanov’s connections with the Hermitage continue, and he is one of the collectors involved with the current Fabergé exhibition at the museum. The exhibition, Fabergé: Jeweller to the Imperial Court, opened at the Hermitage in November 2020, and runs until next month. According to an interview given by Ivanov to ArtNet, the objects for the exhibition were chosen by a Fabergé specialist, Marina Lopato, before her death in July 2020. Some of the objects had been loaned by Ivanov to the Hermitage for the exhibition.

|

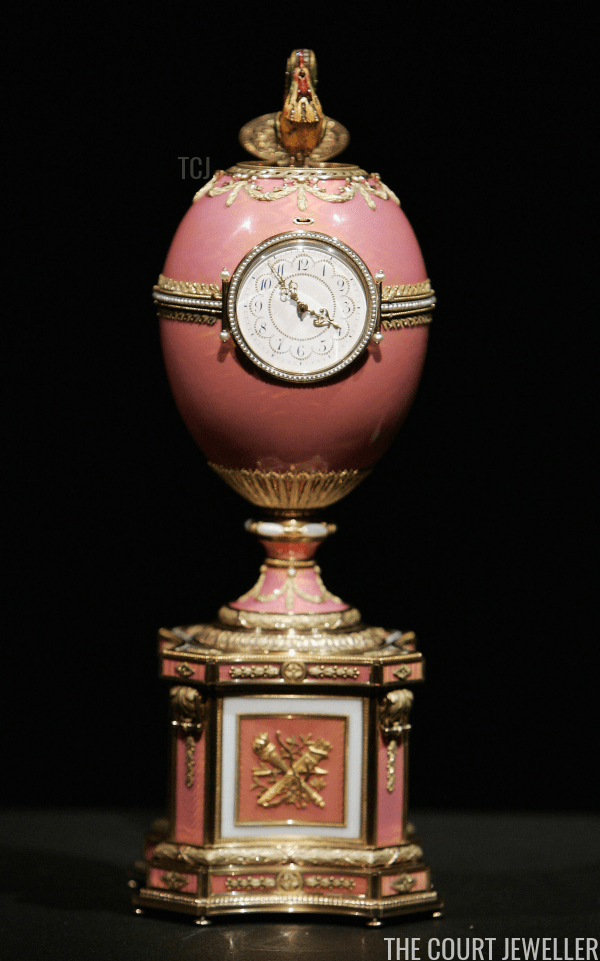

| Ivanov’s Wedding Anniversary Egg in the Hermitage’s catalogue of the exhibition |

One of these Ivanov pieces, the Wedding Anniversary Egg, has been the target of recent criticism from art scholars. The Guardian reports that the egg was “purportedly gifted by Tsar Nicholas II to Empress Alexandra on their 10th wedding anniversary in 1904.” But the egg’s authenticity was called into question in 2020 by an American scholar. DeeAnn Hoff, who published an article noting issues with the egg. Hoff pointed out that some of the portraits on the egg appear to have been based on recent colorized images, including a portrait of Grand Duchess Anastasia that was colorized by Brazilian artist Marina Amaral. The original black-and-white photograph of Anastasia was taken in 1906, two years after the egg’s stated date of creation.

Hoff also noted issues with the image of Nicholas II on the egg, including the number and color of his medals and decorations. Ivanov provided ArtNet with documentation that he claimed would prove the egg’s authenticity, but the publication found discrepancies within that paperwork as well.

|

| Another view of Ivanov’s Wedding Anniversary Egg |

Andre Ruzhnikov, an art dealer based in London who specializes in Fabergé objects, wrote to the Hermitage’s longtime general director, Mikhail Piotrovsky, asking him to close the exhibition in light of the questions about the authenticity of several of the pieces on display. He told the Guardian, “I want the shame to end. I want this show to be closed and forgotten, and that’s it. You cannot subject the Hermitage to such shame.”

Neither Piotrovsky nor any other official spokesperson from the Hermitage has responded to press outlets seeking comment on the matter. Instead, the museum published Piotrovsky’s preface to the exhibition catalogue on its website. In that essay, he notes, “The authenticity of each fresh item that appears on the market can always be disputed and will be. Documents, receipts, the presence of a maker’s mark are no more than a partial help. The consensus of the expert community is not easy to obtain and is often lacking. That is why any kind of new publication is accompanied by discussion,” adding that “every new exhibition brings with it round tables discussing general and specific issues.”

The museum also reproduced the text of an article from a Russian news website, which essentially argues that Ruzhnikov is biased in his claims, partly because of his prior association with another Russian oligarch, Viktor Vekselberg. The owner of the world’s largest private collection of Fabergé eggs, Vekselberg now owns the collection of eggs that once belonged to the Forbes family. He also runs another private museum, the Fabergé Museum in St. Petersburg. The article also includes a quote from Piotrovsky, who appears to be referencing Ruzhnikov’s credentials when he notes, “One needs to bear in mind the enormous difference between art specialists who are dealers and museum art scholars. The occupation of the former is buying and selling, that of the latter is preserving, studying and presenting. For the former a work of art is a commodity; for the latter it’s part of a complex cultural process. Nowadays there is good interaction, but that does have its limits, set by concern about profits for the one group and the pursuit of knowledge for the other.” There’s no mention made in the article of the scholarly work done on Ivanov’s Wedding Anniversary Egg by DeeAnn Hoff.

|

| Christie’s |

The Wedding Anniversary Egg is not the only item included in the exhibition that has been questioned by other Fabergé dealers and researchers. Other eggs, decorative objects, and jewelry have also been flagged as possible fakes. Interestingly, the exhibition includes a sapphire and diamond tiara, which ArtNet notes is “presented at the Hermitage as a work by Fabergé.” When the same tiara was sold at auction at Christie’s in November 2014, there was no link made between the jewel and the Fabergé workshop. Instead, the lot notes from the auction simply describe the piece as “an antique sapphire and diamond tiara/necklace” made around 1890, with floral and fleur-de-lis elements in its design. The auction house did not offer an opinion on the tiara’s maker.

The tiara, which fetched more than $100,000, was offered by an unnamed “gentleman of title” and was presented in a fitted case from S.J. Phillips Ltd., a London antique firm. ArtNet reached out to a “a prominent London Fabergé dealer” for an assessment of the tiara. The dealer, who was granted anonymity by the publication, noted, “It is inconceivable that Russian Empresses, with the unmatched Russian crown jewels at their disposal, would demean themselves with composite low-quality tiaras of this type.”

|

| The Hermitage Museum (Wikimedia Commons) |

At the time of this writing, the exhibition at the Hermitage continues to be open to the public, and no additional response has been made by the museum regarding the charges that some of the objects on display are not authentic. As the hunger for acquiring Fabergé objects continues, especially in Russia, questions over the authenticity of each Fabergé piece will likely be raised time and again. After, all, as Ruzhnikov noted, as long as prices for genuine Fabergé items continue to be high, we’ll also continue to see lots of “Fauxbergé” on the market as well.