|

| Andreas Rentz/Getty Images |

Grace Kelly’s Engagement Rings

|

| Prince Rainier, Grace Kelly, and her parents pose during a press conference announcing Grace and Rainier’s engagement, January 1956 (Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy) |

As Monaco celebrates its National Day today, I’ve got a closer look at two of the most intriguing jewels from the late Princess Grace’s collection: her engagement rings.

|

| Grace shows her engagement ring to her mother, Margaret Kelly, during the engagement press conference, January 1956 (AFP via Getty Images) |

Yes, you read that right: rings, plural. The first, more modest ring was presented to Grace by Prince Rainier when he proposed to her over the Christmas holidays in December 1955/January 1956. The actress and the prince had met the previous May, and they’d carried out a sort of epistolary romance, corresponding across the Atlantic while she filmed movies and he dealt with drama over the insecure succession in Monaco.

|

| Grace shows off her ruby and diamond ring during the press conference in Philadelphia held to officially announce her engagement in January 1956 (Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy) |

A few days after their second in-person meeting, which happened at Christmas in 1955, Rainier offered Grace a diamond and ruby ring from Cartier. The public got a first glimpse at the ring on January 5, 1956, when the engagement was officially announced at a Philadelphia country club. The Philadelphia Inquirer described Grace’s ring during the official press conference: “Grace, wearing a champagne colored dress of wool with gold metallic dots and gold collar clips and earrings, sported a handsome engagement ring, which the Prince had ordered fashioned from two family heirlooms, in the form of a diamond circlet and ruby circlet intertwined.”

|

| Grace wears her second engagement ring in a scene from High Society with Frank Sinatra |

The diamond and ruby engagement ring was described prominently in news reports in the day following the engagement, but when Grace returned to Hollywood to begin filming High Society, another ring suddenly appeared on her finger instead. Press shots from the set on the first days of filming in January 1956 show her wearing an enormous diamond ring while in costume for her role as Tracy Lord.

|

| Grace “polishes” her diamond engagement ring in a scene from High Society |

The press picked up on the ring swap, and Grace addressed the switch in a press interview. She told gossip columnist Louella Parsons that she’d been due to wear an prop diamond ring in High Society, but Rainier had offered her a real one as a second engagement ring. She happily explained, “now I can wear my real engagement ring” in the film, after getting the okay from the film’s director. The Philadelphia Inquirer trumpeted that the ring would be “one of the ‘stars’ of the picture.” One High Society scene, which playfully acknowledged the ring (and, implicitly, the press surrounding Grace during filming), even shows Grace breathing on the ring and polishing it on a pillow.

|

| Grace’s diamond ring, on display with other Cartier jewels at the Denver Art Museum in 2015 |

The second ring was a stunner. Also made by Cartier, it featured a 10.5-carat emerald-cut diamond flanked by a pair of diamond baguettes. (Press articles from 1956 exaggerated the size a bit, calling it a 12-carat diamond.) So why the switch? Grace’s friend Judith Balaban Quine wrote that the original ring had always been intended as a “friendship ring,” a placeholder while a “proper engagement ring” was being made.

|

| Grace wears her diamond engagement ring in a portrait, 1956 (ScreenProd/Photononstop/Alamy) |

Quine also revealed that Grace always knew a bigger ring was coming, and she even suggests that the prop that had been made for High Society served as the inspiration for the real diamond ring Rainier commissioned for Grace. But why hadn’t Rainier simply brought along a traditional diamond engagement ring to America? Just before he sailed back to Europe in March 1956, he told gathered reporters simply that “it is silly to count your chickens before they are hatched.” In the end, both the ruby and diamond friendship ring and the massive diamond engagement ring became regular parts of Grace’s jewelry wardrobe, worn until her death in 1982.

Chaumet in Majesty: Napoleonic Jewels

|

| Photo generously provided by Royal Warren(t); do not reproduce |

I’ve got a major treat for all of you today! Royal Warren(t), one of our readers here at The Court Jeweller, recently visited the grand Chaumet exhibition in Monaco, and she’s offered to share some of her photos with us! The splendor is so great that we’ll be dividing the bounty into two posts. Today’s post features jewelry and other items associated with the reign of Napoleon I.

|

| Wikimedia Commons |

Napoleon Bonaparte became Emperor of France in 1804. He emphasized his rise from modest noble roots to imperial domination through the splendor of his court, including magnificent portraits like Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres’s 1806 painting, which depicted him in his coronation robes. Another easy way to add a little magnificent splendor to your world is, of course, to employ a court jeweler to drape precious stones on both you and the women in your life. Napoleon turned to Marie-Étienne Nitot, a former apprentice of Marie Antoinette’s court jeweler, to do the job, appointing him court jeweler in 1802. (Nitot’s firm would eventually become the present-day house of Chaumet.)

|

| Wikimedia Commons |

The woman at the center of Napoleon’s imperial world in 1802 was, of course, his wife, Josephine de Beauharnais. Marie-Etienne Nitot and his son, Francois-Regnault Nitot, created numerous pieces of jewelry for Josephine during her marriage to Napoleon. Above, Josephine is depicted wearing fashionable jewels and clothing from the period in a portrait completed by François Gérard in 1801. (If you haven’t yet, I’d highly recommend reading Anne Theriault’s fantastic historical articles on Josephine, which are part of her ongoing “Queens of Infamy” series. You’ll find the first one here!)

|

| Photo generously provided by Royal Warren(t); do not reproduce |

At the start of their relationship, however, the jewelry that Napoleon offered to Josephine was a bit humbler. The Chaumet exhibition in Monaco featured this small gold and enamel ring, which features the initials JNB (for Josephine Napoleon Bonaparte) and the inscription “amour sincere” (French for “true love”). The maker of the ring is unknown, but we know that it was presented to Josephine by Napoleon in 1796, the year they married.

|

| Photo generously provided by Royal Warren(t); do not reproduce |

The exhibition also included Napoleon and Josephine’s marriage certificate. He married the elegant older widow, whose first husband had been executed during the Terror, in March 1796, much to the dismay of his mother and sisters.

|

| Photo generously provided by Royal Warren(t); do not reproduce |

Following the custom of the day, Napoleon had a grand wedding basket made for his new wife. The basket, which is made of silk, silver, copper, and papier mâché, was part of the Chaumet exhibition as well, on loan from the museum at Malmaison.

|

| Photo generously provided by Royal Warren(t); do not reproduce |

The wedding basket, or corbeille de mariage, was part of a tradition that dated to the 17th century. The groom’s gifts to his bride were placed in the basket and then presented to her. Notes from the exhibition explained that the basket and gifts were then “exhibited from the morning of the signature of the wedding contract until the day of the ceremony.” The maker of Josephine’s wedding basket is sadly not known.

|

| Photo generously provided by Royal Warren(t); do not reproduce |

We do know, however, the maker of these fantastic acrostic bracelets, which also belonged to Empress Josephine. Francois-Regnault Nitot made them for Josephine in 1806, the year that her son, Eugene de Beauharnais, was officially adopted by Napoleon (and was married off to Princess Augusta of Bavaria). The bracelets use gems to spell out the names of Josephine’s children. The bottom bracelet in the exhibition display spells out “Eugene” using an emerald, an uniaxial crystal (a crystal with a unique axial structure that does not show light), a garnet, an emerald, a nicolo (which is a blue-hued intaglio), and an emerald. The top bracelet spells out the name “Hortense,” for Josephine’s daughter, using a hessonite, an opal, a ruby, a turquoise, an emerald, a nicolo, a sapphire, and an emerald. The year 1806 was also significant for Hortense de Beauharnais; she had agreed to marry Napoleon’s brother, Louis, in 1802, and four years later, he appointed them King and Queen of Holland. (It didn’t last; Louis abdicated in 1810.)

|

| Wikimedia Commons |

1810 turned out to be a pivotal year for the entire French imperial court. That January, Napoleon divorced Josephine, who had been unable to provide him with an heir. He subsequently married Archduchess Marie-Louise of Austria (a great-niece of Marie Antoinette), first by proxy in Vienna, and then in a civil ceremony in Paris, and then in a grand religious ceremony held in the chapel of the Louvre. The scene was documented by the French painter Georges Rouget, in a painting that now hangs in the Palace of Versailles.

|

| Photo generously provided by Royal Warren(t); do not reproduce |

Napoleon’s marshals and their wives wore their finest attire for the imperial wedding ceremony. The Chaumet exhibition featured the gown worn at the wedding by Maréchale Davout, Princess of Eckmühl. Born Aimée Leclerc, she was the sister of General Leclerc, who had been married to Napoleon’s sister, Pauline, until his death in 1802. Aimée became the second wife of Louis-Nicolas Davout, one of Napoleon’s most dedicated marshals, in 1801.

|

| Photo generously provided by Royal Warren(t); do not reproduce |

Although Aimée was known for her thriftiness, she agreed to be dressed by the Parisian couturier Louis-Hippolyte Leroy for the royal wedding in 1810. Leroy produced a remarkable gown of tulle and ivory silk satin embroidered with gold and platinum thread for Aimée. The gown’s permanent home is the Musée d’Eckmühl in Auxerre, having been donated to the city by Aimée’s daughter, the Marquise de Blocqueville.

|

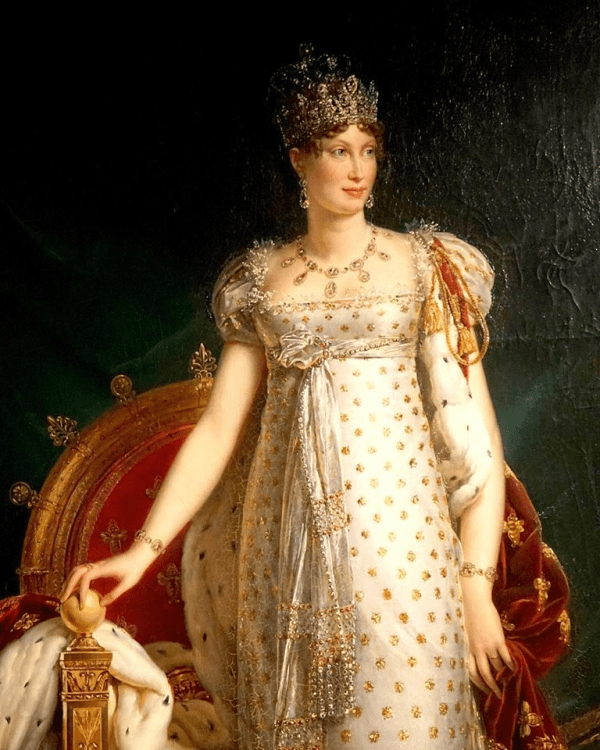

| Wikimedia Commons |

Napoleon’s court jewelers were tasked with supplying regal jewelry to the new Empress Marie-Louise, who often wore complete bejeweled parures in fantastic court portraits. Paintings like this one, completed by Joseph Franque in 1811, emphasized her new status as the emperor’s wife — and, very quickly, as the mother of his child. Napoleon and Marie-Louise’s son, Napoleon II, was born in March 1811, less than a year after his parents’ marriage.

|

| Photo generously provided by Royal Warren(t); do not reproduce |

Marie-Louise’s grand jewelry box contained some fascinating pieces. The Chaumet exhibition included this Gothic belt, made by Francois-Regnault Nitot around 1813 for Marie-Louise. (He became Napoleon’s court jeweler when his father, Marie-Etienne Nitot, died in 1809.) The belt, which reflects the era’s growing interest in neo-Gothic art and design, was made of gold, pearls, and onyx. The long portion of the belt is designed to drop from the waist to the bottom of the wearer’s gown, echoing medieval clothing styles.

|

| Photo generously provided by Royal Warren(t); do not reproduce |

The buckle portion of the Gothic belt features a lovely antique cameo. The cameo had been a gift to Marie-Louise from her sister-in-law, Pauline Bonaparte, who was living in Rome with her second husband, Camillo Borghese, 6th Prince of Sulmona.

|

| Photo generously provided by Royal Warren(t); do not reproduce |

The exhibition also featured jewels worn by courtiers during Napoleon’s second marriage. This amethyst and diamond suite, which features a necklace and coordinating earrings set in silver and gold, belonged to the Comtesse Vilain XIII. The set was made around 1810; no information on the maker is available.

|

| Wikimedia Commons |

The amethysts belonged to Sophie de Felz, one of Empress Marie-Louise’s ladies-in-waiting. She was the wife of the Comte Vilain XIIII, a wealthy Belgian aristocrat and statesman. Sophie was so close to the imperial couple that she held Napoleon and Marie-Louise’s son during his baptism at the Cathedral of Notre-Dame in 1811. The remarkable portrait of Sophie above, which also features her daughter Louise, was painted by Jacques-Louis David in 1816. The painting, done after the fall of Napoleon, was completed in Brussels, where both Sophie and David had taken refuge. Sophie later went on to serve as lady-in-waiting to another royal woman: Queen Louise, wife of King Leopold I of Belgium.

|

| Wikimedia Commons |

The reign of Napoleon coincided with a passion for jeweled parures: complete matching sets of jewelry that featured tiaras, necklaces, earrings, bracelets, brooches, and even hair combs and small coronets. In this portrait, painted by Jean-Baptiste Paulin Guérin around 1812, Marie-Louise wears a complete parure of diamond and topaz jewels.

|

| Photo generously provided by Royal Warren(t); do not reproduce |

In 1811, the Nitot workshop produced a fantastic complete ruby and diamond parure for the Empress. The set included a tiara, a comb, and a small crown as well as a necklace, bracelets, earrings, and even a jeweled belt. This original drawing of the design for the parure was included in the exhibition.

|

| Photo generously provided by Royal Warren(t); do not reproduce |

Also included in the exhibition were replicas of some of the pieces from the parure. The notes accompanying these jewels in the exhibition state that the pieces were “made in the Nitot et Fils ateliers in memory of the ruby and diamond parure commission delivered to Empress Marie-Louise on January 16, 1811.” Instead of diamonds and rubies, these gold and silver replicas are set with white sapphires, zircons, and garnets.

|

| Photo generously provided by Royal Warren(t); do not reproduce |

Here’s a closer look at the replica tiara and comb. The rubies are represented by garnets in these replica jewels.

|

| Photo generously provided by Royal Warren(t); do not reproduce |

And here you’ll see the necklace, girandole earrings, and bracelets. (The garnets look very dark, almost black, in photographs — but if you look closely at the top bracelet, you’ll see the red color of the stone coming to life.) Nearly the entirety of the real diamond and ruby parure has been lost, having been first completely remodeled and then sold at auction in 1887, but two pieces survive: the diamond and ruby bracelets.

|

| Wikimedia Commons |

Marie-Louise’s tenure as Empress of France ended in 1814 with Napoleon’s abdication at Fontainebleau. She left the country with her son, settling first in her native Austria and then in Italy, where she ruled as Duchess of Parma. (Francois-Regnault Nitot also left France at the end of Napoleon’s reign, selling his jewelry business to Jean-Baptiste Fossin.) Meanwhile, Marie-Louise’s diamond and ruby set remained back in France. The bracelets from the suite were renovated for the use of another royal woman: Madame Royale, the only surviving child of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. She married her first cousin, the Duke of Angoulême, in 1799. She was technically Queen of France for twenty minutes on August 2, 1830 — the time that elapsed between the abdication of her father-in-law, King Charles X, and her husband’s subsequent abdication.

|

| Wikimedia Commons |

Today, the diamond and ruby bracelets worn by Empress Marie-Louise and the Duchess of Angoulême still reside in a French palace: the Louvre Museum. The bracelets are on display alongside the grand emerald tiara also from the Duchess’s collection.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- …

- 95

- Next Page »