“Paterfamilias,” episode 9 of The Crown‘s second season, is light on jewelry but heavy on (very altered) “history.” Before we dive in, you can catch up on our previous recaps over here!

We open in 1962. The Queen is having tea at Windsor Castle with the headmaster of Cheam, where Prince Charles has been going to school.

The Queen (wearing a production-invented ribbon brooch) is dismayed to hear that Charles has been isolated and bullied at the school, in part because of his royal title and in part because of his sensitive nature. The headmaster suggests that Charles should be sent to Eton College for senior school, in part because it’s in Windsor.

(The person who actually advocated most for Charles to go to Eton was the Queen Mother. According to the Sally Bedell Smith biography of Prince Charles, the Queen Mum wrote to her daughter in May 1961, calling Eton “ideal” for Charles. I’m guessing the show’s version of the Queen Mum is too busy watching television to take an interest in her grandson.)

Elizabeth talks to Charles about Eton and shows him how close it is to the castle. He’s excited.

And even Uncle Dickie gets in on the school preparations, taking Charles to Savile Row to have his uniforms tailored.

Wearing a production-created pearly brooch, Elizabeth is happy as she shares the plans for Charles’s next educational step with Philip.

But he’s angry at the suggestion that Charles should go anywhere but his own alma mater, Gordonstoun. He pulls rank and demands that Charles be placed there. Elizabeth ultimately agrees, but she says he has to inform Charles of the change.

He tells his son about Gordonstoun, the school run by a headmaster, Kurt Hahn, where “the sons of the powerful can be emancipated from the prison of privilege.” He even gives Charles his old uniform jumper.

And then we flash back three decades to 1934, where Philip puts on the jumper for the first time. He’s at Schloss Wolfsgarten in Germany, the home of his sister, Princess Cecilie of Greece and Denmark (called “Cécile”), and her husband, Georg Donatus of Hesse (called “Don”). As his armband suggests, he was indeed a member of the Nazi party, but the timeline’s not quite right — Don and Cécile didn’t join the party until 1937.

Cécile, who is so afraid of flying that she dresses in funereal black each time she boards an airplane, accompanies Philip to Scotland so he can start at Gordonstoun.

The show is playing very fast and loose with history in this episode, mostly to try to make Don and Cécile seem like pivotal parental figures to Philip in an attempt to increase the drama of their eventual deaths. He did spend time with them at their home, mainly on school holidays, but they were only two of the adult family members with whom he stayed during his childhood. Philip had been in school at Cheam in the United Kingdom from 1929 until 1933, and he’d lived during that period with his grandmother, Victoria, and with other British family members. (His official guardian at the time wasn’t Cécile — it was his uncle George, the Marquess of Milford Haven.) His father, Prince Andrew of Greece and Denmark, also made fairly frequent, if sometimes irregular, appearances in his life. (His mother, Princess Alice, was in a clinic in Switzerland during much of this period.)

In 1933, Philip transferred to a German school, Salem, which was run by Kurt Hahn. (This was apparently largely for financial reasons; the Baden family, which included his sister, Princess Theodora, and her husband, Berthold, owned the school, so Philip saved on fees.) Eventually, worries in the family about the rise of the Nazis meant that he’d go back to Britain for the remainder of his education. Around the same time, Hahn (who was Jewish) was arrested and later fled to Scotland, where he founded Gordonstoun.

Philip did arrive at Gordonstoun in the autumn of 1934, but I’ve never read any suggestion that Cécile accompanied him there — this, again, mostly seems like narrative invention to try to create dramatic tension. (I have read, however, that it was actually another sister, Princess Theodora, who took Philip to Scotland.)

Cécile also tells him backstory about Kurt Hahn — a person Philip had already met in reality — largely, I think, to inform in the viewer. She tells him that he’s going to Gordonstoun because “Father” wanted him to be educated by Hahn — sure, but Philip already had been educated by Hahn at Salem, and as I stated above, Andrew does not seem to have been a pivotal part of that decision.

When Philip arrives at Gordonstoun, he seems surprised by the way the school is run, even though he’d already been at its German counterpart. This fellow student is surprised that Philip doesn’t have a surname.

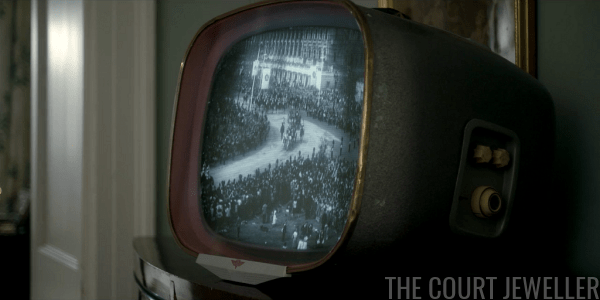

And then we’re back in 1962. Philip flies Charles to Gordonstoun himself, while Elizabeth is left behind. (That’s true.) In pearls, she watches footage of her son’s arrival at school on television.

A thought: there’s something interesting to be said about the number of times this show features women (even a head of state!) passively watching current events on television rather than participating in them.

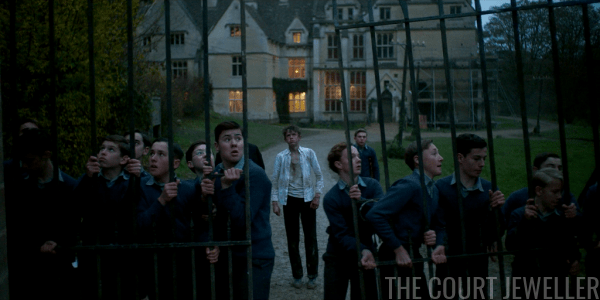

Charles faces down his immediate future at Gordonstoun, and things aren’t looking good.

British boarding schools weren’t easy places to live (to put it mildly), and Gordonstoun was especially tough. Boys slept with the windows open in all kinds of weather, and the dormitories were basically run by older students, who often bullied and even abused their younger counterparts. Charles shivers his way through his first night, sleeping in the same bed his father did when he was a student.

Back in 1934, Philip learns the ropes at Gordonstoun, including their tradition of cold showers after a morning run through the mud. Such fun. (This would have been nothing new. He’d already experienced similar unpleasant boarding school traditions at both Cheam and Salem.)

He also faces a bully, who makes fun of Philip’s parents and his sisters — and then tosses him in a lake.

He’s called in to Hahn’s office for a talk. I’m pretty disappointed that they didn’t go with a more accurate portrayal of Hahn here — the real man wore a cape and a big black hat and was, by all accounts, pretty eccentric. The Hahn shown in The Crown could easily be swapped out for one of the production’s cabinet ministers. A really wasted characterization moment, if you ask me.

Philip calls Cécile, begging to come back to Germany. She tells him that she’s having another baby. (That means that the production has condensed the timeline, and we’re skipping ahead to 1937. Cécile was expecting her fourth child; she already had three others: Ludwig [born in 1931], Alexander [born in 1933], and Johanna [born in 1936].)

She also tells him that “Cousin Lu” — that’s Don’s brother, Ludwig — is getting married during Philip’s half term in London, and she’ll stay back in Germany so that Philip can come stay with her. (Lu’s wedding to Margaret Campbell Geddes, daughter of Sir Auckland Geddes, was originally scheduled for October 23, 1937. It was initially postponed until November 20, 1937, following the death of Lu’s father [and Philip’s great-uncle], Grand Duke Ernst of Hesse.)

Back in 1962, Charles is also having a tough time at school. Uncle Dickie arrives with a hamper from Fortnum and Mason and a sympathetic ear. He tells Charles to trust him as a confidant, underscoring the important relationship the two really did have until Dickie’s death.

Elizabeth has heard about Charles’s misery at Gordonstoun, and she confronts Philip, threatening to remove Charles and bring him back home. Philip absolutely refuses her request.

Meanwhile, Charles gets a visit from Hahn. (Hahn still lived in the UK in 1962, but he hadn’t been headmaster at Gordonstoun for almost a decade.) He’s worried that Charles is trying to take on the school’s annual challenge just to please his father. Charles insists he can do it.

In 1934/7/whatever, Philip also has a meeting with Hahn. This time, Philip has punched his bully, and Hahn is unhappy about it. He cancels Philip’s half-term vacation to Germany and orders him to spend his vacation working with the bully to build a wall at the front gate.

Philip relates this news on the telephone to Cécile. Now that Philip’s not coming, she’s got to go to the wedding in England, and she’s getting ready to board the plane.

The idea that Cécile would have stayed in Germany — and avoided the ensuing tragedy — if only Philip had behaved himself is absolute nonsense. The show is simplifying this period of family history in a major way. On November 12, 1937, a large funeral was held in Darmstadt for Cécile’s late father-in-law, and on the same day, she wrote to Uncle Dickie thanking him in advance for hosting her family during Lu’s upcoming wedding festivities. There was no suggestion that Philip would be going to Germany, or that Cécile wouldn’t be going to the wedding. Honestly, I think it’s a little irresponsible, even in this fictional form, for the show to depict Young Philip believing that what happened next was his fault. The real history is tragic enough.

After Philip speaks to Cécile, we see Hahn receiving a phone call. It’s not good news. The plane carrying Don, Cécile, and their family to London has crashed in Belgium, and there are no survivors. (That dates this scene to November 16, 1937.)

He tells Philip, who isolates himself in his grief. Later, he reportedly expressed that the news was a “profound shock.” (He really was at Gordonstoun when he was informed of the accident.)

In his grief, Philip imagines that he can see the crash happening around him. Everyone on the plane, including Don, Cécile, their two sons, Don’s mother, Lu’s best man, a lady-in-waiting, and the flight crew, perished. The remains of Cécile’s stillborn baby boy were also found in the wreckage. (Two family tiaras, the Hesse Strawberry Leaf and the Turquoise and Moonstone, survived.)

He wanders away from Gordonstoun, and Hahn and the other students finally find him rowing a boat alone on the lake. Hahn tells him that he’ll be on a train shortly to make his way to Darmstadt for the funeral.

(The next day, Lu married Peg Geddes in London in a somber ceremony. He had lost both his parents, his brother, his sister-in-law, and three nephews in only a few weeks’ time. When he and Peg arrived in Germany, they adopted Don and Cécile’s only surviving daughter, Johanna — but she died less than two years later of meningitis. Not a lot of luck, this family.)

In Darmstadt, Philip walks behind Don and Cécile’s coffins in their funeral procession. (The show paints him as a solitary figure — and the chief mourner. Neither was true. Lu Hesse was the chief mourner in the procession.)

The show depicts Philip’s parents, Andrew and Alice, walking behind the coffins, as well as Uncle Dickie. All three really did attend the funeral, though I’m doubtful that Alice walked in the procession. (This was the first time Alice and Andrew had seen each other in 1931 — and it was also the last time they’d see each other.) Lord Mountbatten was there in an official capacity, representing King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. (Queen Mary was represented by Philip’s grandmother, the Dowager Marchioness of Milford Haven.)

Uncle Dickie comforts Philip, who is overwhelmed both by his sister’s death and by the Nazi propaganda all around him.

And then there’s this scene. Philip’s sister, Princess Sophie, tries to get Alice to recognize him — but to no avail.

This is also ridiculous. Alice was actually doing fairly well at this period — she’d been able to attend her Uncle Ernie’s funeral a few days earlier, and she coped with the shock of Cécile’s death better than most had hoped she would. According to the excellent Hugo Vickers biography, Theodora told Alice’s doctor, “The first curative shock to her was brought about by the plane-crash…. Contrary to what was expected, it apparently tore her out of everything.” Philip had even been urged to get in touch with his mother about his plans for Christmas 1937, so that he could spend time with her. She absolutely knew who he was. But I suppose catatonic Alice was more convenient for the narrative?

The show could also have made links with Alice in the “present-day” 1962 context. She visited London in February of that year while Philip was off on a tour of South America. She was there while Charles recovered from having his appendix removed, and she even attended little Prince Andrew’s second birthday party. Or — going back an episode — Alice even attended that dinner held at Buckingham Palace for the Kennedys. Ah, what might have been, show.

And even worse — Prince Andrew stands up, in front of everyone, and actually blames Philip for Cécile’s death.

I can’t overstate how ridiculous this is. Andrew was in London when the crash happened; he’d been staying with his nephew, King George II of Greece. Philip traveled with his father to the funeral in Darmstadt. Andrew did have a hard time coping with Cécile’s death, because the two were very close, but he had no reason to blame Philip for the accident.

Philip heads back to England, accompanied by Uncle Dickie. (His grandmother, Victoria, would also surely have been with them.) Dickie gives Philip a little paternal advice: one day, when Philip has children, he will disappoint them as deeply as Andrew has just disappointed him. Cheerful, Dickie.

Underscoring the ridiculousness of this entire interlude is Philip’s travel schedule from the end of 1937 and the beginning of 1938. After spending Christmas in the UK, Philip traveled to Rome to meet up with his father. From there, Andrew, Philip, and two of Philip’s sisters, Margarita and Theodora, all went together to Athens for the wedding of Prince Paul of Greece and Princess Friederike of Hanover, which took place on January 9, 1938.

But the show’s version of Philip is alone at Gordonstoun, and he works through his grief by building that wall at the front gate. He works alone until his body almost literally gives out, and then finally goes inside to ask for help.

Hahn, pleased that Philip has seen the value of the community around him, instructs the other students to help Philip finish the project.

Back in the 1960s, an older Philip stands in front of a smug portrait of himself as he prepares to award a trophy to the winners of the school challenge. He waits expectantly to see Charles return with his group.

But Charles doesn’t come back, and his detective, Donald Green, has to go and find him. He offers a shivering Charles a comforting arm in the back of the room when they return. (Green was like a father figure to Charles, and Smith argues that their friendship “set the prince’s lifelong pattern of seeking company with his elders.”)

Still angry at his son, Philip flies them back to Windsor. He is utterly unsympathetic when Charles (like Cécile) is frightened of the turbulence mid-flight. Charles ends up sobbing in the back of the plane.

And when he returns to Windsor, Charles rushes back to the comfort of his nanny and the palace staff.

His mother simply looks on — and then leaves without saying hello.