|

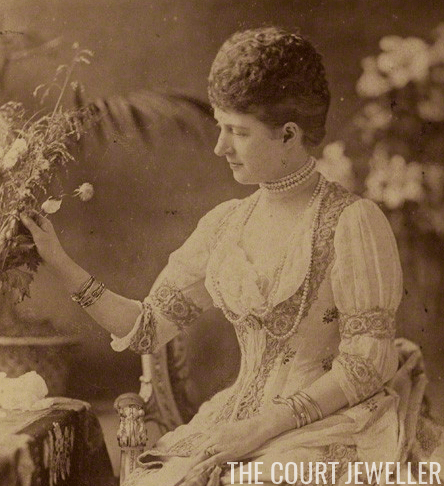

| Detail, Louis Pierson’s photographic portrait of the Countess of Castiglione, ca. 1860 |

A few superstitious Spaniards believe that the long series of misfortunes that has befallen Spain and the present dynasty follows a cursed opal ring that a neglected beauty spitefully bestowed upon poor Alfonso XII [1] some four-and-twenty years ago. This is the story:

“It is an opal of large size and of most brilliant coloring, with a spark of living fire in its center. It is set in filigree gold, and has no other jewels about it. The ring belonged to that famous beauty and adventuress, the Comtesse de Castiglione [2], who was the most beautiful woman Europe ever knew, and who was in the glory of her loveliness and power during the reign of Napoleon III [3]. The Emperor was her abject slave and aroused the most violent jealousy on the part of Eugenie [4]. This dazzling woman was present at all the great functions of the Tuileries [5], and displayed her superb shoulders and bust in bewildering relief by the lowness of her corsages.

|

| King Alfonso XII of Spain, ca. 1870s |

“Every diplomat and statesman in France was at her feet, and among her most ardent admirers was Alfonso XII, then an outcast and a pretender [6]. The bewitching Comtesse did not spend much of her time with him at first, but when she found his chances for becoming King of Spain were good, she smiled on him, and his head was completely turned. When he went to his throne, the Comtesse was to follow later, according to agreement, and the King promised her a high position at court and his exclusive royal favor. In the meantime, the King had fallen sincerely and deeply in love with one of his own royal blood, and his marriage took place amid much pomp and circumstance [7], and the beautiful Comtesse in Paris was forgotten. It does not pay to pique a woman like this beauty of Castiglione, and her hatred was terrible,” says the veracious chronicler.

|

| King Alfonso XII’s first wife, Mercedes of Orleans |

“A few months after the King’s marriage, he received a package from the Comtesse containing a beautiful opal ring of rare coloring. It was called a wedding gift and a memento of the friendship the King had held for the Comtesse. The King showed it to his wife, Queen Mercedes, who was charmed with its beauty and begged to keep it. Alfonso gave it to her readily, and she slipped it on her finger. From that moment she pined away. In a few months, she died [8]. The ring fell from her dead hand, and the King, who could not bear to see it, gave it to his grandmother, Queen Christina, who died a few months later [9].

|

| Alfonso and Mercedes’s shared grandmother, Maria Cristina of the Two Sicilies |

“Next the ring was given to Alfonso’s sister, the Infanta Maria del Pilar, who wore it but a few days before she died of a mysterious illness [10]. The King then gave the fatal jewel to his sister-in-law, the youngest daughter of the Duc and Duchesse de Montpensier, and in three months, the young princess was dead [11]. After this series of fatalities, the King determined to keep the ring himself, and he slipped it on his little finger. From that moment his health began to fail, and in twenty-four hours, he was dead [12].

|

| Alfonso XII’s second wife, Maria Cristina, and their children, Mercedes, Maria Teresa, and Alfonso XIII |

“The doctors pronounced his case one of the strangest on record. His whole physical system seemed to have crumbled away, every vital organ of his body having suddenly succumbed to the most marked senile decay. Physicians could never account for it, and the matter was hushed up [13]. Queen Christina, who is not in any way superstitious, took possession of the ring after her husband’s death, but the other members of the family, with dark Spanish superstition, begged her to destroy it.

|

| Queen Maria Cristina and King Alfonso XIII |

“This she refused to do, but to prevent it from doing other damage, she hung it about the neck of the patron saint of Madrid, where it is today [14]. The Spaniards, however, are not satisfied yet, for they declare that the fatal ring influences the saint to evil things. They credit the war with the United States to the ring [15], and the Queen Regent had been begged to destroy it or send it out of the country. If the Queen is well advised, she will surely take one of the courses suggested, for what country could expect to conquer while cursed by a ring like this, governed by a King who is the thirteenth of his line [15]?”

NOTES

1. King Alfonso XII (1857-1885) reigned in Spain from 1874 until his death in 1885. He was the only son of Queen Isabella II; although his father was officially Isabella’s husband, King Francis, many speculate that Alfonso was actually the son of a captain of the guard.

2. Virginia Oldoini, Countess of Castiglione (1837-1899) was an Italian aristocrat and mistress of Emperor Napoleon III of France. A famous court beauty, she was an important figure in the early history of photography. Because she had so many important and powerful connections, she’s also thought to have been possibly involved in secret diplomatic missions.

3. Napoleon III (1808-1873) was President of the French Second Republic from 1848 to 1852 and Emperor of the French Second Empire from 1852 to 1870. His father was Louis Bonaparte, younger brother of Napoleon Bonaparte; his mother, Hortense de Beauharnais, was the daughter of Empress Josephine. He was exiled after the Franco-Prussian War and settled in England, where he died.

4. Eugenie de Montijo (1826-1920) was a Spanish aristocrat; through her marriage to Napoleon III, she was Empress of France from 1852 to 1870. After the family was exiled, she lived out most of the rest of her life in England. She was the godmother of Queen Victoria Eugenie of Spain.

5. The Palais des Tuileries was the Parisian residence of French kings and emperors for several centuries. It was burned to the ground in 1871, but its extensive gardens still exist and are open to the public today. A reconstruction of the palace has been proposed at various times during the past decade, in part of help expand the exhibition space of the Louvre Museum.

6. The Spanish Revolution of 1868 forced Queen Isabella II and the royal family into exile, and Alfonso relocated to Paris with his mother. He studied for a time in Vienna, but in 1870, his mother officially abdicated, making him the pretender to the Spanish throne. He returned to Paris to become a monarch-in-pretense at the French imperial court — which then collapsed with the defeat of the French in the Franco-Prussian war a few months later. Alfonso went to Sandhurst, the famous military academy in England, at the behest of Spanish monarchists. In December 1874, he returned to Spain and reclaimed his throne.

7. Alfonso married his first cousin, Princess Maria de las Mercedes of Orléans, in 1878 in Madrid. Their mothers were sisters. Through her father, Mercedes was a French princess; through her mother, she was a member of the extended Spanish royal family. Her marriage to Alfonso made her Spain’s queen consort.

8. Well, sure — except that, immediately after her wedding, people realized that Queen Mercedes was already suffering from typhoid fever. And then, on top of that, she suffered a miscarriage. She died in June 1878, six months after her wedding and two days after her eighteenth birthday. But maybe it was a cursed opal? (It wasn’t.)

9. Maria Cristina of the Two Sicilies (1806-1878) was Spain’s queen consort from 1829 to 1833 (as the wife of her, uh, uncle, King Ferdinand VII) and the regent for her daughter, Queen Isabella II, from 1833 to 1840. She was the grandmother of both King Alfonso XII and Queen Mercedes. She was also 72 years old and ill when she died in France in August 1878. But maybe it was a cursed opal? (It wasn’t.)

10. Infanta Maria del Pilar of Spain (1861-1879) was Queen Isabella II’s sixth child. She was eighteen when she died, probably of tuberculosis, in August 1879. (Guys, I know this is looking like a pattern, but come on. No need to put the blame on a poor opal when you’re dealing with the health of the always-transient and often-intermarried 19th century Spanish royal family.)

11. Okay, here the “veracious chronicler” gets some of his facts confused. After the death of Queen Mercedes, Alfonso XII was engaged to her elder sister, Princess Maria Cristina of Orléans — and then before they could marry, she died. (Of course. This family’s luck was the worst. But maybe they should have stopped marrying each other?) But her death happened in April 1879, several months before Pilar’s death. Also, Maria Cristina died of tuberculosis, not a cursed opal.

12. Alfonso XII next smartly decided to woo a more distant cousin, Archduchess Maria Christina of Austria (1858-1929). They married in Madrid in November 1879 — and survived an assassination attempt during their honeymoon, naturally. They had two daughters, and Queen Maria Cristina was expecting a son (the future King Alfonso XIII) when Alfonso, who already had tuberculosis, suffered an attack of dysentery and died at the age of twenty-seven. I’m just saying, everybody: I think you’re more likely to die from a one-two punch of tuberculosis and dysentery than from wearing an opal ring, even if it was cursed by a very fancy aristocratic spy.

13. They definitely could account for it. He had tuberculosis and dysentery!

14. Was the opal ring real? Did Queen Maria Cristina really place it around the neck of the icon of the Virgin of Almudena? We may never know. The statue was apparently destroyed in the 1930s during the Spanish Civil War. Which — okay, if even the statue “died,” maybe there’s something to this curse business after all?!?

15. That’d be the Spanish-American War, fought between Spain and the United States in 1898. Spain … um, they lost.

16. If you hoped that King Alfonso XIII, the posthumous son of the much-cursed King Alfonso XII, could brighten up this tale, well, get ready for more disappointment. He ended up losing his throne and died in exile; on top of that, his wife, Princess Ena of Battenberg, was a carrier of hemophilia, and two of their sons inherited the condition. The current royal family in Spain has a whole passel of issues, but compared to the unfortunate history of their ancestors, those problems pale a bit in comparison. (Really, though, guys. It wasn’t the opal!)