|

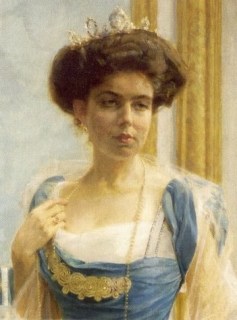

| Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna (the Elder) of Russia |

Review: Diamonds: A Jubilee Celebration

|

| Caroline de Guitaut’s Diamonds: A Jubilee Celebration (2012) [1] |

|

| Queen Elizabeth II [2] |

NOTES, PHOTO CREDITS, AND LINKS

1. Image of book cover from Amazon.com.

Margaret of Connaught’s Khedive Tiara

|

| Crown Princess Margareta, ca. 1908 [1] |

|

| Margaret of Connaught [2] |

The Khedive tiara’s story begins even before the piece’s creation. Margaret, the niece of King Edward VII of the United Kingdom, was on a royal tour with her parents, who wanted to marry their daughters off to suitable royal spouses. They had their eye on the future king of Sweden, Gustaf VI Adolf, as a prospective partner for Margaret’s sister, Princess Patricia. They rendezvous-ed with Gustaf Adolf in Cairo, where he immediately fell in love — but with the wrong sister. It didn’t matter, in the end; Margaret was in love with him, too. Gustaf Adolf proposed to her during a dinner at the British consulate in Cairo, and the two were married at Windsor in 1905.

As the young couple had met in his country, it was important that the Khedive of Egypt — the governor of the country, which was ruled by the British at the time — give them a suitable wedding present. He commissioned Cartier to make this tiara for the occasion. The piece, which has alternately been described as a scroll tiara and as a tiara featuring marguerite motifs, bears considerable similarity to another piece made for the Egyptians at roughly the same time: Princess Shwikar’s tiara. That piece has never been firmly attributed to Cartier, but I wouldn’t be surprised at all if the same jeweler was behind both sparklers.

|

| Illustration of the tiara/ornament from Margaret of Connaught’s wedding gifts [3] |

|

| Ingrid of Denmark [5] |

So far, the bridal wearers of the Khedive have been Queen Margrethe II of Denmark (see here); Princess Benedikte of Sayn-Wittgenstein-Berleburg (see here); Benedikte’s two daughters, Princess Alexandra (here) and Princess Nathalie (here); Queen Anne-Marie of Greece (see here); and her elder daughter, Princess Alexia (here). Anne-Marie’s younger daughter, Princess Theodora, will also be eligible to wear the tiara if she marries. After Ingrid’s death in 2000, she left the tiara to her younger daughter, Anne-Marie, the former queen of Greece. Anne-Marie has had alterations made to the base of the piece [6], so that it sits much higher now on the wearer’s head (you can clearly see these changes in wedding photos of Nathalie of Sayn-Wittgenstein-Berleburg, the only bride to have worn it so far after it was altered).

It will be extremely interesting to see what happens to the Khedive tiara in the next generation. Will Anne-Marie leave it to one of her daughters, who are no longer princesses of a reigning monarchy? Will it be returned to the Danes, to preserve it officially as a wedding tiara for the next generation of royal brides? (That will include three Danish princesses — Isabella, Josephine, and Athena — as well as the granddaughters of Benedikte and Anne-Marie.) Cases like the Khedive, which has both historical and familial importance, make me wish that Ingrid had followed the example of Juliana of the Netherlands and set up a foundation for her jewelry. But for now, only time will tell [7].

NOTES, PHOTO CREDITS, AND LINKS

1. Cropped version of photograph in the public domain; source here. (The Grand Ladies website suggests that the photograph may have been made to advertise Margaret to potential grooms, but if the photo really was taken in 1908, that’s not possible.)

2. Portrait of Crown Princess Margareta of Sweden by Axel Jungstedt, ca. 1909; source here.

3. Detail of the illustrated newspaper guide to Margaret’s wedding gifts; a full version of the image available here.

4. Here’s an image of Frederik and Ingrid on their wedding day in 1935. While neither Margaret nor Ingrid wore the Khedive as a bridal tiara, they both wore the same Irish lace veil that Margaret had been given as a wedding gift. All of Ingrid’s female descendants, plus Crown Princess Mary, have also worn the veil on their wedding days. In a bit of morbid trivia, the same veil covered Margaret of Connaught’s body in her coffin, though the veil was removed before the coffin was closed so that it could be given to Ingrid.

5. Cropped version of photograph available via Wikimedia Commons; source here.

6. See the tiara’s new base here.

7. A version of this post originally appeared at A Tiara a Day in February 2013.