Time for another peek into the bejeweled world of PBS’s Victoria, magpies! Today we’ve got a recap of episode three, “Warp and Weft.” (Catch up on our previous recaps here!)

Everyone’s up in arms about a boy who has managed to break in to Buckingham Palace. Victoria, who wears a large era-appropriate brooch while having tea with Albert and Baby Vicky, isn’t taking it too seriously, and that ticks Albert off.

He can’t believe how badly the palace is run, and he is thrilled when Victoria gives him permission to make some reforms. Albert loved nothing more than reform! He spends much of this episode arguing with the various staff members who are in charge with different parts of the palace, but he ends up deciding that it’s time to raise the servants’ wages.

At Brocket Hall, Melbourne still isn’t feeling well. A doctor comes from London, but he doesn’t have good news — because Melbourne’s condition is so uncertain, he advises Lord M to put his affairs in order. (Melbourne had a stroke in October 1842.)

Victoria and Emma Portman, both wearing hair combs, are also both worried about Melbourne, and Victoria asks Emma to go and check on him.

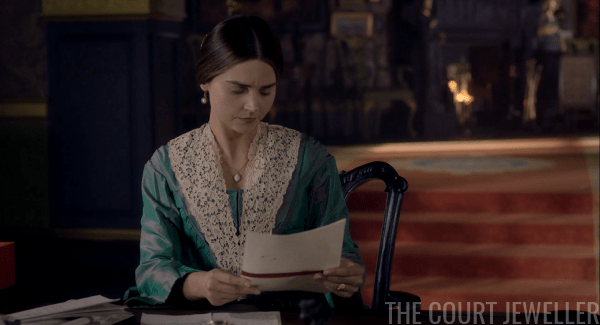

Charlotte Buccleuch, cameo in tow, brings Victoria her correspondence. Among the letters is one from a Mr. Bascombe, who wove the silk for Victoria’s wedding dress. She agrees to have an audience with him.

Victoire Kent, who has been dressed in mourning clothes and jewels for some reason this season, watches warily.

Emma goes to see Lord Melbourne. He makes various excuses for his absence from court and correspondence. She’s not buying it.

Mr. Bascombe comes to the palace, lobbying on behalf of his fellow silkmakers in Spitalfields.

He doesn’t want the country to import silk from other countries, and he shows her samples for quality comparison. (Note that she’s moved the brooch from her first outfit to her waist on this dress.)

Victoria is displeased when Peel won’t promise to protect the industry. But Drummond, in between flirty glances with Lord Alfred, suggests another solution: throw a ball, and draw attention to the weavers of Spitalfields by requiring all guests to wear their silk. Peel warns that such an event might not be popular with all classes of society, even invoking Marie Antoinette. Victoria throws the Corn Laws in his face, and resolves to proceed with the plan. (Plans for this ball, historically, took place in the spring of 1842, several months after the birth of King Edward VII, with whom she is pregnant in this episode.)

That night, pearl-and-brooch-clad Wilhelmina gazes lovingly at Ernst as he plays the piano, basically the same scene we’ve had between the two of them for three episodes now.

Wearing a production-invented necklace and that very modern brooch, Victoria tells everyone about her plans for the ball. Charlotte Buccleuch is horrified at the idea that Victoria would dance in her “condition.” Victoria finds a reason to casually dismiss her from the room.

Ernst has an idea for the ball: he thinks it should be Plantagenet themed, following the fashions worn at the court of King Edward III. Albert’s still not sure it’s a good idea to hold a ball when so many of Victoria’s subjects are suffering. She counters that the ball, designed to help local trade and industry, will be beneficial.

Invitations go out, including one to Lord Melborne. He scowls.

Albert, Victoria, and their entourage visit Westminster Abbey to see the tombs of King Edward III and Queen Philippa. The guide tells them a story that illustrates Philippa’s influence over her husband.

Wilhelmina takes the opportunity to quiz Ernst about his costume for the ball. She suggests Robin Hood, and he thinks portraying an outlaw would be just about perfect.

Emma visits Melbourne to tell him about the ball preparations. He’s decided he’ll come to the ball after all.

Garrard (the crown jeweler during Victoria’s reign) gets a reference when Victoria presents Albert with a special part of his costume for the ball: his own crown. (He’s going as Edward III, she’s going as Philippa.)

We get a montage of the silk weavers creating the fabric for Victoria’s costume and Victoria herself trying on her gown and jewels. Over it all, a member of parliament rails against the excesses of the ball.

Victoria and Albert get dressed and ready for the ball. This Plantagenet ball was a real event, held on May 12, 1842. You can see their real costumes from the ball in the Landseer portrait here.

Note that the costume designers chose to put Victoria in a faux ruby-and-diamond necklace rather than the pearl necklace depicted in the portrait.

The ball is beautiful, but lots of people are unhappy. Peel is worried about the national mood. Charlotte Buccleuch thinks the whole thing is just an excuse for Albert to pretend to be king. And then Harriet Sutherland shows up at the ball on her husband’s arm. (They both really attended.) Ernst convinces her to dance with him. (He wasn’t really there; he married Princess Alexandrine of Baden in Germany the very next day!) Wilhelmina (still fictional) is crushed…

…but she’s soon buoyed by attentions from Lord Alfred, who has also been flirting again with Mr. Drummond.

Another surprise guest also arrives: an ailing Lord Melbourne, in disguise as Dante. (Melbourne really did attend the ball.) Victoria chastises him for not answering her letters.

Peel (who also really attended the ball) grows more and more disgusted by the excess all around him.

And it turns out he’s right about the national mood — the people are not happy with such an extravagant palace ball, no matter how much business it gave to the silk weavers.

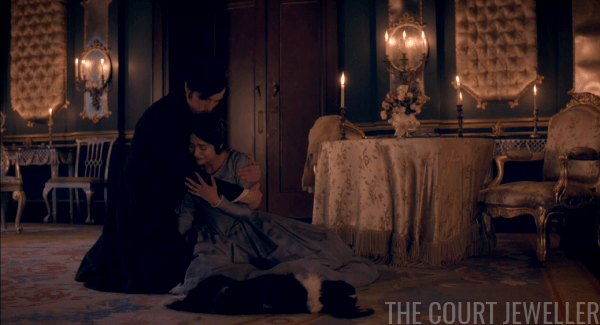

Back inside, Victoria convinces Melbourne to waltz with her. Emma has to help cover for him when he becomes ill during the dance.

And then Victoria catches a glimpse of the growing mob outside the palace. She realizes she’s seriously misjudged the situation.

After the ball, Albert’s happy to discard his crown.

Morning dawns, and Victoria, still in her Plantagenet dress, surveys the aftermath of her big silk party. She’s disgusted by the waste, and she decides to give the leftovers to the poor. Hope they like half-melted ice sculptures!

The press is scathing in their criticism of the ball, much to Victoria’s frustration. Emma interrupts her with a request: she needs to take a leave of absence to help her sister following a difficult birth. Victoria quickly agrees. (Conveniently, her sister lives right next door to Brocket Hall.)

Also departing: Ernst, who’s heading back to Coburg. (As I mentioned above, he’d been back in Germany for a while — on May 13, 1842, he married Princess Alexandrine of Baden in Karlsruhe.)

Peel reminds Albert that he can do good things without a crown of his own. He suggests that Albert should start by working with the people building the new Houses of Parliament. (Fire destroyed parliament in 1834, and the rebuilding project began in 1840. The following year, Prince Albert headed a committee that worked on the interior design of the new building.)

Victoria visits Mr. Bascombe’s workshop in Spitalfields to discuss the effects of the ball. She’s pleased to hear that they’ve seen positive effects, and orders have gone up.

Albert heads to Westminster Hall, where he runs into Melbourne, who is clearly suffering. Melbourne thinks Albert’s a good choice to be the patron of the new parliamentary building project.

Harriet and her ferronniere miss Ernst terribly, and it’s mutual. (Still lamenting the missed opportunities with her character. She was an important, influential figure in Victorian society, and she was an ardent abolitionist.)

Albert comes home and tells Victoria that he’s seen Melbourne. Although he’s promised not to, Albert confesses that Melbourne is seriously ill. She promises Albert that she won’t tell anyone that she knows.

But she does stop by Melbourne’s London house before he heads back to the countryside and gives him a gift: a mechanical singing bird. They both clearly know that she knows about his illness, but neither says anything direct about it.

They share a sentimental goodbye.

An even worse goodbye is waiting for Victoria at the palace. Dash, who has been showing his age, has died. (In reality, he died at the end of 1840.) Albert tries his best to comfort her. “Everything changes,” he explains, “except us.” (Ooh, Albert, that’s terrible foreshadowing.)