This week, The Gilded Age, a new television series from Downton Abbey creator Julian Fellowes, premiered in the US on HBO. In honor of the long-awaited arrival of the show, I’m going to be showcasing famous jewels from the Gilded Age on selected days over the next several weeks here at The Court Jeweller. We’re kicking things off with a big one: the diamond tiara that belonged to Consuelo Vanderbilt, the American heiress who became Duchess of Marlborough in 1895.

Consuelo Vanderbilt, born in New York in 1877, was the first child of William Kissam Vanderbilt (grandson of the Commodore, Cornelius Vanderbilt) and his first wife, Alva Erskine Smith. W.K. Vanderbilt inherited a boatload of family money and took control of the Vanderbilt railroad empire. The family lived in an elaborate, castle-like home on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan (built in 1883), and their other homes included Marble House, their “summer cottage” in Newport, Rhode Island.

Consuelo and her two younger brothers were raised in the very lap of luxury. When the family’s mansion at 660 Fifth Avenue was completed in the spring of 1883, Alva Vanderbilt threw a masquerade ball for a thousand of her closest friends in the ballroom. By 1888, even British newspapers were reporting on little Consuelo’s glittering future: “Ten years hence a famous belle in New York will be Miss Consuelo Vanderbilt. All the conditions are favourable. Miss Vanderbilt will then be just making her formal debut in society. The wealth of her father, William K. Vanderbilt, may easily have grown to forty million pounds. Her mother will have passed over from the ranks of gay young wifehood into matronliness, and therefore be willing to put her daughter forward into her own former place as a belle.”

It didn’t take ten years. Suitors for the wealthy, eligible young woman came calling early and often. Still a teenager, Consuelo was sought by Prince Francis Joseph of Battenberg, a brother of Prince Alexander of Bulgaria and Prince Louis of Battenberg (later the 1st Marquess of Milford Haven). She turned him down, and he married a Montenegrin princess instead. Consuelo’s young heart had been captured by an American beau, Winthrop Rutherfurd. He was part of New York’s social elite, but Consuelo’s mother was aiming higher than that for a match for her daughter.

Determined to end Consuelo and Winthrop’s romance, Alva took her daughter to England. Alva knew well that there was a high demand for wealth American wives for cash-strapped British aristocrats, because one of her best friends, the heiress Consuelo Yznaga (who was also the godmother and namesake of Consuelo Vanderbilt), had married the future Duke of Manchester in 1875. In London, Alva enlisted the aid of Lady Paget, the American-born hostess who had become a prominent matchmaker for American heiresses and titled British men. Alva and Minnie zeroed in on Charles Spencer-Churchill, the 9th Duke of Marlborough as a good candidate. “Sunny,” as he was known, had inherited a dukedom that was on the brink of financial collapse. Alva wanted a title; Sunny needed an heiress. In their minds, it was a match made in heaven.

For Consuelo, it was more like the match from hell. She was deeply in love with Rutherfurd, and she had to be convinced—perhaps forcibly, depending on which version of the story you read—to marry Marlborough. The wedding took place on November 6, 1895, at St. Thomas’s Church in New York. The groom was nearly 24, and the bride was only 18. She wore an incredible bridal confection of satin and lace. When the two were pronounced husband and wife, she became the Duchess of Marlborough, and he became the proud owner of $2.5 million in railroad stock, plus an additional $100,000 annual income for life. (She also received a $100,000 annual income in the deal.) On their honeymoon, he confessed that he too was in love with someone else, and he’d only married her to save the family estate. Romantic!

Newspapers breathlessly covered every second of the wedding day. One American reporter enthused, “The wedding was in all its appointments simply gorgeous, even the minutest detail being carried out with the utmost lavishness. Certainly no similar function ever held in New York, has excited so vast an amount of public interest as this,” adding, “Money for the event has flowed as freely as water.”

The Vanderbilts had indeed spared no expense. This was Alva’s moment: not only to launch her daughter into the aristocratic social stratosphere, but to shore up her own social position as well. Not even a year before the wedding, Consuelo’s parents had divorced. Alva had accused her husband of flagrant adultery, and she’d received a $10 million divorce settlement. In January 1896, just weeks after Consuelo’s glittering marriage ceremony, Alva married again, this time to Oliver Hazard Perry Belmont. William Vanderbilt would go on to remarry as well, though he waited until 1903. His new wife, Anne Harriman, was Winthrop Rutherfurd’s sister-in-law.

Some of the incredible Vanderbilt money was splashed out on the purchase of a glittering new tiara for the young duchess. The tiara was acquired from Boucheron for Consuelo by her father as a wedding present. In her autobiography, The Glitter and the Gold, she describes the jewels she received as part of her trousseau: “It was then the fashion to wear dog-collars; mine was of pearls and had nineteen rows, with high diamond clasps which rasped my neck. My mother had given me all the pearls she had received from my father. There were two fine rows which had once belonged to Catherine of Russia and to the Empress Eugénie, and also a sautoir which I could clasp round my waist. A diamond tiara capped with pearl-shaped stones was my father’s gift to me, and from Marlborough came a diamond belt.”

The biography, produced by Consuelo with the help of a ghostwriter in the 1950s, is well known for its tendency toward exaggeration. But her descriptions of the physical discomfort caused by these grand new jewels echo the words of other women who wore similarly extravagant pieces. She stated that her tiara and jewels “were beautiful indeed, but jewels never gave me pleasure and my heavy tiara invariably produced a violent headache, my dog-collar a chafed neck.” Perhaps someone entering into a happy marriage filled with love could have been able to overlook the pain of wearing the jewels. For Consuelo, it seems only to have added to her misery.

Shortly after arriving in England, the new Duchess of Marlborough was presented at court to Queen Victoria. Consuelo recalled, “For my presentation, my wedding dress had been cut low and with the court train looked bridal and festive. Around my waist was the diamond belt my husband had given me and on my head a diamond tiara; there were also pearls in profusion.” The new American duchess made a splash in society, and newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic carried reports of her appearances at prominent social functions.

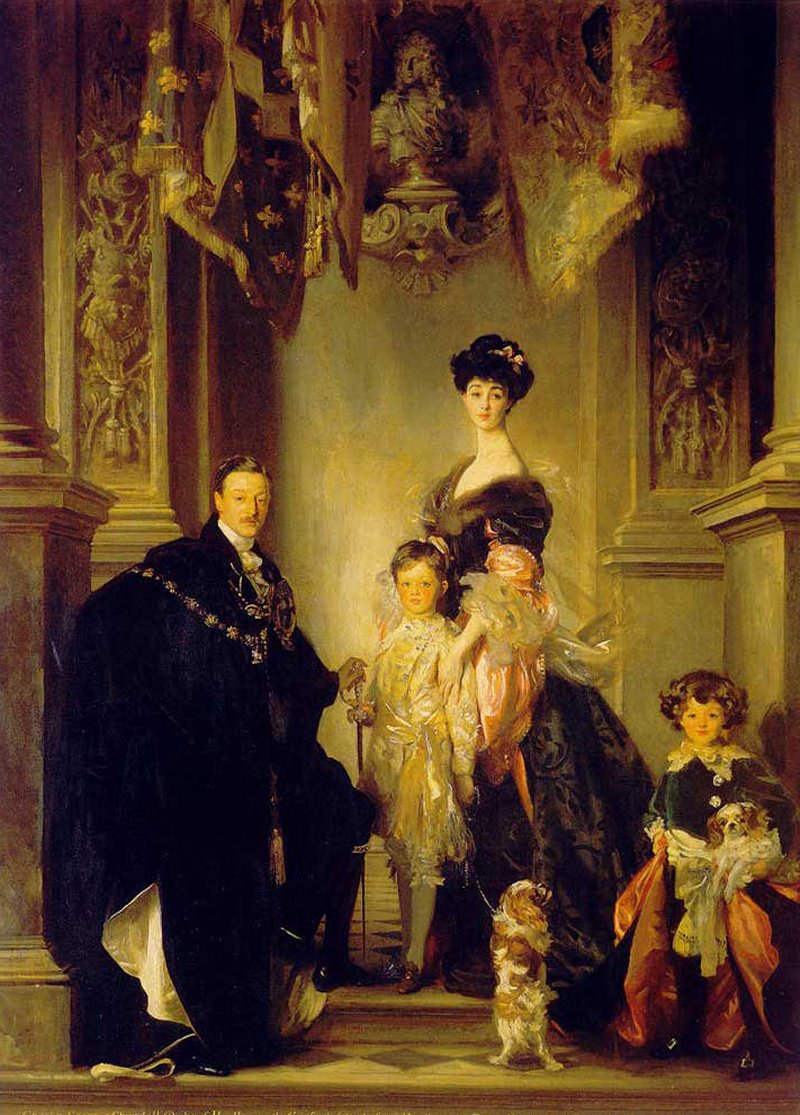

The union of Consuelo and the Duke was one of those infamous “buccaneer” marriages of the Gilded Age—the rich American bride would bring with her a substantial dowry that would help fix crumbling manor homes and pay off debts, while the aristocratic British husband would bring with him a title and status for his new wife. Consuelo’s money did manage to save Blenheim Palace, the ancestral home of the Dukes of Marlborough. Above, the Duke and Duchess are immortalized in splendor with their children in a portrait by John Singer Sargent from 1905. The painting is still part of the collection at Blenheim today.

Though the Marlborough marriage did produce two sons—John, who would later become the 10th Duke of Marlborough, and Ivor—it was ultimately unhappy from start to finish. Both parties were unfaithful. There were even rumors that Ivor was fathered by someone else (namely, Winthrop Rutherfurd, the man Consuelo had been romancing before her wedding to the Duke).

Even so, Consuelo became socially prominent, and she wore her Boucheron tiara at some of the most important gatherings of British society in the Edwardian era. Perhaps most significantly, she wore the piece at the coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra in 1902. She also added several other pieces from her bridal trousseau to her coronation ensemble, including the remarkable 19-stranded pearl choker necklace and the diamond belt.

The public gobbled up newspaper descriptions of the lavish attire worn by royals and aristocrats for the coronation, which took place in August 1902. Consuelo was described as wearing “the loveliest lace and embroidery ornamentation upon white satin,” adding that she also wore the “Vanderbilt pearls in roped festoons and superb diamonds,” which “sparkled all over her corsage and far below her waist.” She also wore her diamond crescent ornament on the bodice of her gown.

Mindful of the size of her diamond tiara, Consuelo later recalled that she’d gone to significant trouble to have a coronet made that would fit perfectly inside the tiara’s circumference. She remembered that, when the monarch was crowned, “I fitted it deftly to its place and watched with amusement the anguished efforts of others whose coronets were either too big or too small to stay in place.”

As Duchess of Marlborough, Consuelo was one of four peeresses who had the honor of holding a canopy over Queen Alexandra’s head during the 1902 coronation ceremony. The moment was immortalized in a painting by the Danish artist Laurits Tuxen. You’ll spot Consuelo standing to the right of Queen Alexandra, who kneels for the anointing ceremony. The Boucheron tiara, with its distinctive pear-shaped diamond toppers, can be seen sparkling on Consuelo’s head. The other three canopy bearers depicted are the Duchess of Portland, the Duchess of Montrose, and the Duchess of Sutherland. (You’ll also spot several royal ladies looking on from the box above.)

By the next coronation, which took place in June 1911, the Marlborough marriage was effectively over. The couple had separated in 1906. At the time, press reports about the separation noted that the couple had no plans to divorce. Consuelo continued to carry on with her public life, including numerous charitable endeavors. But the marital separation did cause some in the wider social world to exclude Consuelo from various functions. The most prominent of these “snubs” came in the spring of 1911, when Queen Mary decided not to name Consuelo as one of the canopy bearers for her coronation.

The other three duchesses who had performed the role in 1902—Portland, Montrose, and Sutherland—were all asked to reprise their parts. Consuelo, though, was replaced by the Duchess of Hamilton. The Washington Post reported, “The only reason why the Duchess of Marlborough has never been invited to serve is because of her separation from her husband, to which must likewise be ascribed her absence from all great court functions. Indeed, it is doubtful, under the circumstances, and in view of the strict rules that prevailed during the Victorian reign, and that have been revived by King George and Queen Mary, whether the duchess will receive her summons as a peeress of the realm, to the coronation.”

But Consuelo did attend the coronation. One witness reportedly said that the Duchess “came in like a storm cloud” as she entered the abbey for the coronation ceremony. Above, she poses in her tiara and coronation robes—one paper reported that she wore “the entire Vanderbilt regalia” for the occasion—with her sons, John and Ivor.

Consuelo’s autobiography tells one additional story about her tiara—or, more properly, her lack of tiara. She recalled a dinner with King Edward VII, then Prince of Wales, for which she decided to wear her diamond crescent in her hair instead of her tiara. She wrote, “The Prince with a severe glance at my crescent observed, ‘The Princess has taken the trouble to wear a tiara. Why have you not done so?’ Luckily I could truthfully answer that I had been delayed by some charitable function in the country and that I had found the bank in which I kept my tiara closed on my arrival in London.”

By 1919, Consuelo’s marriage was nearly at an official end, and so was her connection with this tiara. In December of that year, she auctioned her tiara at Christie’s in London. The New York Times report on the sale describes the tiara as a “magnificent brilliant tiara, of foliage and scrollwork design and surmounted by nineteen large, pear-shaped stones of the finest quality.” The piece was purchased for £23,000 by S.H. Harris & Son, a Bond Street jewelry firm. The firm bought the tiara specifically to break it up and reuse the diamonds. The Times write-up also observes: “The auction room was crowded with women. The suggestion is made that the Duchess sold the ornament because tiaras are becoming old-fashioned.” In reality, Consuelo sold the tiara just before her divorce proceedings began.

Consuelo’s glittering aristocratic marriage officially ended in 1921. At the Duke’s request, they also pursued an annulment, which was granted in 1926. By that time, Consuelo had married a second time, to the French aviator Jacques Balsan. They’re pictured above together at their French chateau in the 1930s. Consuelo died in New York in 1965, but her eternal resting place is back across the pond. She’s buried in Oxfordshire, near her sons, in the parish that includes Blenheim Palace. There, her descendants continue to live as the Dukes of Marlborough today.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.