With the recent premiere of the new Julian Fellowes series in America, everyone’s talking about the Gilded Age. Our series of articles on the jewels of the era continues today with a look at a spectacular tiara that was worn by two American-born Duchesses of Manchester.

Our story today begins with one of the very first “buccaneer” brides to take the British aristocracy by storm: Consuelo Yznaga. Consuelo’s parents were part of wealthy families from Cuba and Louisiana, and Consuelo was raised in Concordia Parish. Even so, her parents were focused on maintaining their place in high society, purchasing homes in New York and Newport and traveling to Paris. Their close friends included Alva Vanderbilt, who made Consuelo the godmother of her daughter, Consuelo Vanderbilt.

Consuelo’s family’s desire for social prominence reached its greatest height when Consuelo snagged a title. In 1875, Viscount Mandeville, son of the Duke of Manchester, was traveling in the United States. He and Consuelo met at one of her father’s homes, and within a few months, they became engaged. On the face of it, the marriage was mutually beneficial for both parties. Consuelo and her family wanted a title and status; Mandeville needed money. Their wedding, held in May 1876 at Grace Church in Manhattan, was a glittering society event.

But from the start, Mandeville proved himself to be less than a prize. Gail MacColl and Carol McD. Wallace note that “Mandeville’s profligate behavior had already spoiled his chances for a respectable English match” before he met Consuelo. He was an alcoholic and a spendthrift. The couple had three children—a son, William, and twin daughters, May and Nell—and in 1890, on his father’s death, they became the Duke and Duchess of Manchester. The new 8th Duke’s lifestyle, though, quickly caught up with him. He was declared bankrupt just as he inherited his father’s title, and he died in 1892.

Consuelo found herself a widow at the age of only 39. But she remained a popular figure in London society—and reportedly became a mistress of the Prince of Wales, who ascended to the throne as King Edward VII in 1901. Two years later, Consuelo commissioned a grand new tiara for herself from Cartier’s workshop in Paris. Set with more than 1400 diamonds, which Consuelo supplied herself, the tiara was created with a design of flaming hearts and graduated scrolls. The ends of the tiara feature scrolls in the shape of the letter C, for Consuelo’s name.

Here’s a view of the back of the tiara. Diamond drops are suspended from the center of each heart, and small diamond tassel designs are nestled between the hearts. Newspapers afterward were full of references to Consuelo wearing a spectacular diamond tiara at various gala events. For example, in January 1905, accounts of a ball at Chatsworth House, attended by the King and Queen, included a mention of Consuelo wearing “a white taffeta toilette, with an over gown of white gauze glittering with tiny silver sequins, and her necklace and tiara were of diamonds.”

In this portrait, Consuelo wears her tiara with a fashionable diamond choker necklace and a second necklace of diamonds with festoons and pendants. You really get an idea of the scale of the enormous Cartier tiara in this portrait.

Consuelo’s twin daughters passed away in 1895 and 1900, leaving her with only her eldest son, William, the 9th Duke of Manchester. Sadly, he had inherited many of the tendencies and behaviors of his father. He headed to America to try to replicate his father’s luck in marrying a wealthy heiress. There, he met Helena Zimmerman, the only child of Eugene Zimmerman, a wealthy industrialist from Cincinnati who had made his fortune in railroads and oil.

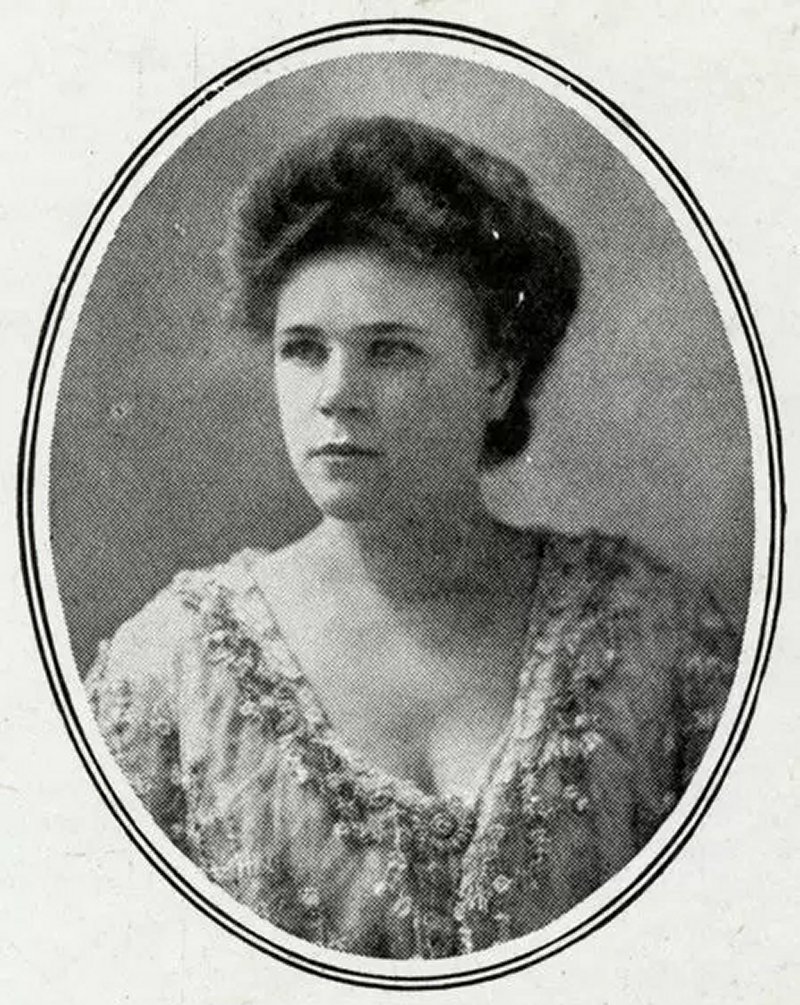

Helena was described in the press as having a “fiery temperament” and a rebellious spirit. This made her a dangerous match for the young Duke of Manchester. Newspapers reported their engagement, and her father loudly denied it. To the shock and displeasure of both of their parents, Helena and the Duke decided to marry in London in secret in 1901. If the Duke had been hoping to receive an enormous dowry after marrying Helena, he was disappointed. Eugene Zimmerman finally did agree to pay off his son-in-law’s debts, but he carefully shielded the money by purchasing various estates owned by the Duke, placing them in trust for Helena and William’s eldest son, who was born in October 1902.

In 1909, Consuelo, the Dowager Duchess of Manchester, passed away. Her jewels were subsequently worn by her daughter-in-law. Above, Helena poses in her jewels and robes for the coronation of King George V and Queen Mary in 1911. The grand Cartier tiara of flaming hearts is the spotlight of her ensemble, looking even larger on her than it had on her mother-in-law. You’ll also spot both of Consuelo’s necklaces from that earlier portrait in this image, including that impressive diamond choker necklace.

From that diamond choker, Helena suspended yet another piece of heirloom jewelry. This diamond and emerald necklace, made in 1860, was one of Consuelo’s wedding gifts in 1876. The necklace was displayed for several years at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, and in June 2020, it was sold at Sotheby’s.

Helena and William’s marriage plodded along for three decades, although they had essentially separated in 1914. William continued to spend excessively, and he was a familiar figure in the bankruptcy courts throughout their marriage. The couple finally divorced in 1931. That December, he married a former stage actress, Kathleen Dawes, in a ceremony in Connecticut. Six years later, Helena also remarried. Her second wedding brought her a new title: her new husband was the 10th Earl of Kintore, making her a countess.

As the 21st century dawned, the Manchester Tiara returned to the spotlight. It was displayed as part of the landmark tiara exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum in 2002. Four years later, in 2006, the 13th Duke of Manchester asked Christie’s to negotiate the sale of the tiara to the museum, where it remained on display. In Hidden Gems, a fantastic book on jewelry sales at Christie’s, Sarah Hue-Williams and Raymond Sancroft-Baker note, “At the time the Duke’s representative approached us, the magnificent family tiara was on loan to the V&A Museum, where it featured as part of the permanent display of their world-class jewellery collection.”

Ultimately, the museum did acquire the tiara from the Duke. The collection notes for the piece on the museum’s website state that it was “accepted by HM Government in Lieu of Inheritance Tax and allocated to the Victoria and Albert Museum, 2007.”

Today, the tiara is one of the highlights of the museum’s incredible jewelry galleries, on display with important royal and noble jewels from around the world. Next time you make a visit to the museum, be sure to stop by to see the tiara, and to remember its fascinating links to a pair of American duchesses from the Gilded Age.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.