One hundred years ago today, the streets of London were filled with well-wishers who had gathered to catch a glimpse of a royal bride. Princess Mary, the only daughter of King George V and Queen Mary of the United Kingdom, married Viscount Lascelles in a glittering ceremony at Westminster Abbey, one of the first major royal weddings held after the end of World War I. Today, to celebrate the centenary of the event, we’ve got a closer look at the wedding day—plus some of the magnificent bejeweled gifts that the royal bride received.

Princess Victoria Alexandra Alice Mary, who was always called by her fourth name, was the third child of King George and Queen Mary. Born in 1897, she followed two brothers, the Prince of Wales (King Edward VIII, later Duke of Windsor) and the Duke of York (King George VI), who would both reign as monarchs. Three more brothers—the Duke of Gloucester, the Duke of Kent, and Prince John—followed her, though John did not survive to adulthood. The princess was named for her great-grandmother, Queen Victoria; her paternal grandmother, Queen Alexandra; her great-aunt, the late Grand Duchess Alice of Hesse and by Rhine (whose birthday she shared); and her maternal grandmother, the Duchess of Teck.

In the photographic portrait above, taken in 1923, King George and Queen Mary are pictured with their surviving children. Princess Mary and Queen Mary are seated in the front row. Behind them are the Prince of Wales, the Duke of Gloucester, King George, the Duke of York, and the Duke of Kent.

Princess Mary had a childhood typical of a royal princess of her era. She was educated at home by governesses, mainly on subjects that were thought to be most relevant for a woman of her time. She was only 17 when war broke out in August 1914, but she would find real purpose in supporting military and charity causes during the conflict. During the first Christmas holiday of the war, she launched an appeal to fund a gift for each person serving in the armed forces. Princess Mary’s Christmas Gift Boxes were distributed to every sailor and soldier serving in the war. The small metal boxes contained sweets, tobacco, Christmas cards, and photographs of the young princess.

Back at home, Princess Mary joined her mother in championing initiatives like the Girl Guides and the Women’s Land Army. And then, in 1918, Mary herself took things a step further, signing up for a nursing course and working at a hospital in London. Later that year, she became the first member of the British royal family to visit France after the end of the war. A week after the signing of the Armistice, she made visits to hospitals and nursing units along the now-quiet front.

One of the soldiers fighting in the war was an aristocratic diplomat from Yorkshire. Henry Lascelles, Viscount Lascelles (the elder son of the 5th Earl of Harewood) was an Eton-educated officer who had graduated from Sandhurst in 1902 before being commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Grenadier Guards. After his service ended in 1905, he had embarked on a diplomatic career. But the war sent him back to the military, first with the reserves and then a second tenure with the Grenadier Guards. Born in 1882, Henry was 32 when he went to the front in April 1915. He saw the worst of the war up close. He was wounded three times and gassed twice, but he survived. He was given both the Distinguished Service Order and the Croix de Guerre for his heroic service.

After the war, the gallant soldier and the wartime nurse, who were both horse lovers, met for the first time at the Grand National, and eventually, they struck up a romance. For the past two generations, the British royals had become more and more open to the idea of letting princesses choose husbands who were not royal. Mary’s great-aunt, Princess Louise, had married the Duke of Argyll, and her aunt, also Princess Louise, had married the Duke of Fife. More recently, Mary’s cousin, Princess Patricia of Connaught, had married Commander Alexander Ramsay, one of her father’s aides-de-camp. She’d given up her title and style, becoming Lady Patricia Ramsay.

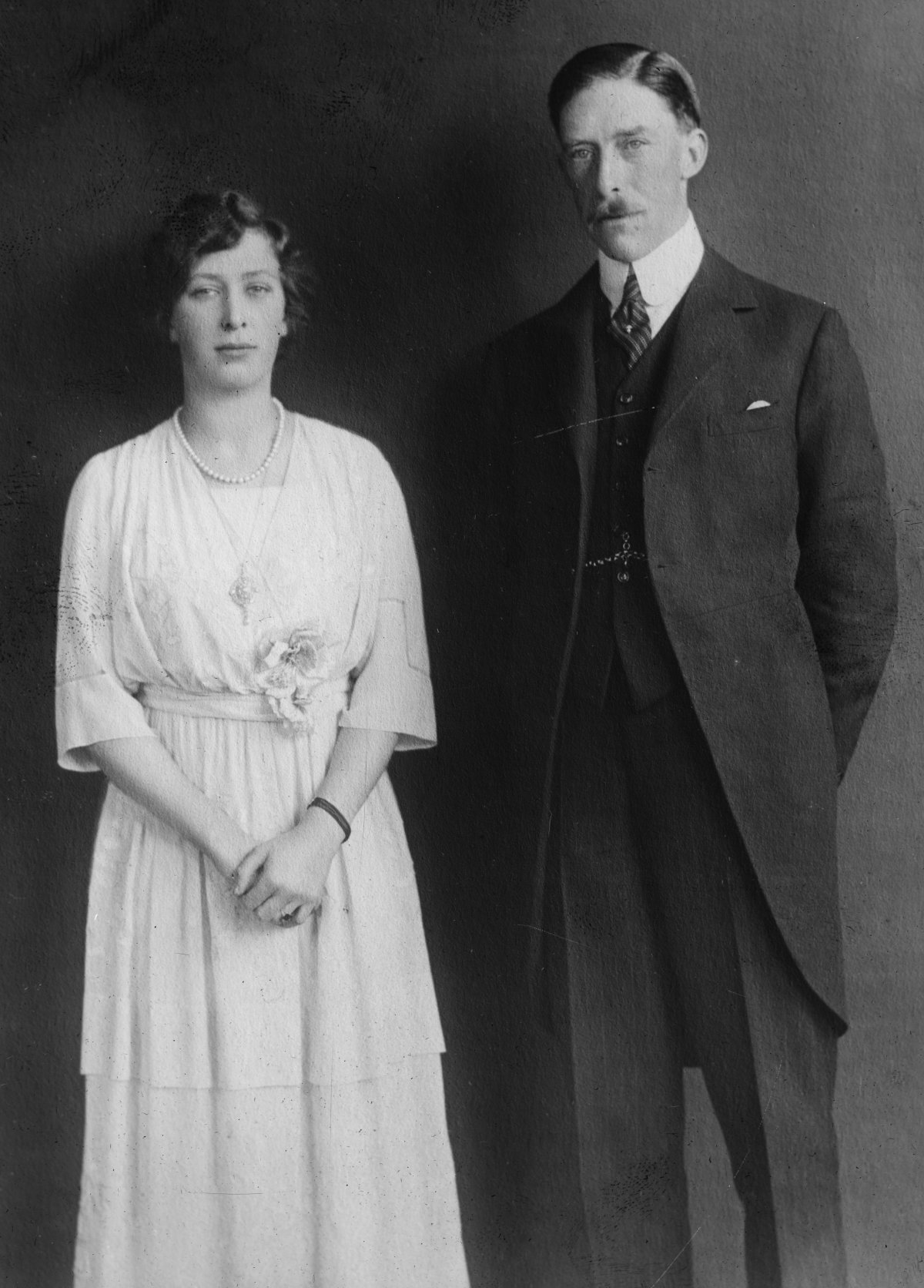

So when the public learned that 39-year-old Lord Lascelles and 24-year-old Princess Mary were engaged to be married, there were no major concerns about a commoner marrying the king’s only daughter. Henry offered Mary a square-cut emerald engagement ring, and their betrothal was announced to the public in November 1921. The Scotsman wrote, “The secret of the attachment between Princess Mary and Viscount Lascelles, and the probability of a formal engagement, has been well kept, but it has not been by any means a secret in Court circles, and in that respect the announcement made…is not in any sense sudden. Viscount Lascelles and his future bride have been seeing a great deal of each other for some time past. Both have been members of parties at various country houses, and Viscount Lascelles has been staying with the Royal Family at Sandringham.” There was a significant age difference between the couple—15 years—but their elder son would write later that the two shared many common interests.

The date for the wedding was fixed soon after, and London planned for grand celebrations on February 28, 1922. This was one of the first big royal weddings after the war, and the city celebrated heartily. Decorations and banners went up in the city, with the couple’s initials, H and M, featured prominently, as on the columns above. Crowds gathered thickly along the procession route to cheer the princess and her father as they rode to Westminster Abbey for the ceremony, and the bride and groom as they headed to Paddington Station after the wedding.

Inside the Abbey, two thousand guests gathered to witness the marriage. Invitations had gone out to royals, aristocrats, and statesmen. Above, Winston and Clementine Churchill arrive for the ceremony.

And here’s the bride, riding in a horse-drawn carriage with her father on her way to the Abbey.

The procession passed by the Cenotaph, the war memorial that had been completed and dedicated only a little more than a year earlier.

Inside the Abbey, the bride and groom were married by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Randall Davidson. Both Henry and Mary spoke their vows in clear, distinct voices. The press made special note of the fact that Mary promised to “obey” her new husband. The Dundee Courier noted that Mary “looked calm but very happy.”

Back at Buckingham Palace after the ceremony, the newlyweds posed for formal official portraits. The groom was distinguished in his uniform with the Garter, which had been given to him by his new father-in-law before the wedding, but Mary’s wedding dress was, of course, the star of the show. One paper described the gown as follows: “Over cloth of woven silver falls a straight slip of net, picoted in silver, and heavily encrusted with pearls in a design of raised roses, and held in place by a girdle of twisted silver and pearls. The dress is ankle length, and a large cluster and trail of orange blossom rests on the hip.

“The veil is outlined with tiny pearls and rare old lace, which also falls over the shoulders with cape-like effect. This lace, the gift of the Queen, was worn by Her Majesty and by her mother before her on their wedding days. The train is four yards long, and specially embroidered with symbols of the Empire. There are the lotus flowers of India worked in heavy silver, the rose of England, the shamrock and thistle, the wattle flower of Australia, the tree fern for New Zealand, and a daffodil for Wales. Here and there is a tracing of blue for happiness.”

With her gown, Mary wore a single strand of pearls and a glittering diamond négligée brooch/pendant, which was a wedding gift from her new husband. The other small pin affixed near the neckline of her gown is a brooch given to her by the Royal Scots regiment when she became their Colonel-in-Chief. Her wedding ring was made from Welsh gold, a tradition for British royal brides.

Mary didn’t wear a tiara for her wedding—at the time, it wasn’t fashionable. Instead, she wore a headpiece to secure her veil. It featured a triple wreath of orange blossoms.

Here, the newly married couple poses for an official portrait with the bride’s parents, Queen Mary and King George. Queen Mary’s jewels include the Cullinan III and IV Brooch (now worn by Queen Elizabeth II) and the Diamond and Pearl Lattice Choker Necklace (now worn by Princess Anne), as well as additional diamond necklaces. She’s also wearing the jeweled garter from the Order of the Garter Insignia on her left arm.

And here they are with their bridal party. Henry’s best man was Major Sir Victor Mackenzie, a British army officer and aristocrat who had attended Sandhurst with Henry and who had also served gallantly in the war. Mary had eight bridesmaids. In the front row are Lady Mary Cambridge (daughter of the 2nd Marquess of Cambridge), Princess Maud (daughter of Princess Louise, Duchess of Fife), Lady Rachel Cavendish (daughter of the 9th Duke of Devonshire), and Lady Mary Thynne (daughter of the 5th Marquess of Bath). In the second row are Lady Doris Gordon-Lennox (daughter of the 8th Duke of Richmond), Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon (daughter of the 14th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne), Lady Diana Bridgeman (daughter of the 5th Earl of Bradford and cousin of the groom), and Lady May Cambridge (daughter of the Earl of Athlone).

Of course, the most notable of the bridesmaids was Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon. The following year, Elizabeth married Princess Mary’s brother, the Duke of York. They later became King George VI and Queen Elizabeth of the United Kingdom, and she was Queen Mother for a half century after his death. At this point, she’d already refused one of Bertie’s proposals, and she would soon refuse the second. She wasn’t persuaded to accept until January 1923.

In this photograph, you’ll see a small brooch pinned to her silver and blue bridesmaid dress. This was a gift from Lord Lascelles to each bridesmaid, and it featured the couple’s initials in sapphires and diamonds.

The bride and groom appeared on the balcony of Buckingham Palace to greet the crowds after the wedding. They were joined by Mary’s parents, King George and Queen Mary, and her grandmother, Queen Alexandra.

Princess Mary may not have worn a tiara on her wedding day, but her wedding gift collection included several tiaras. Among them was a diamond fringe tiara, presented to her by Lord and Lady Inchcape.

King George and Queen Mary offered their daughter a remarkable present: the sapphire and diamond coronet designed by Prince Albert for Queen Victoria. They also gave her several other sapphire pieces to form a suite.

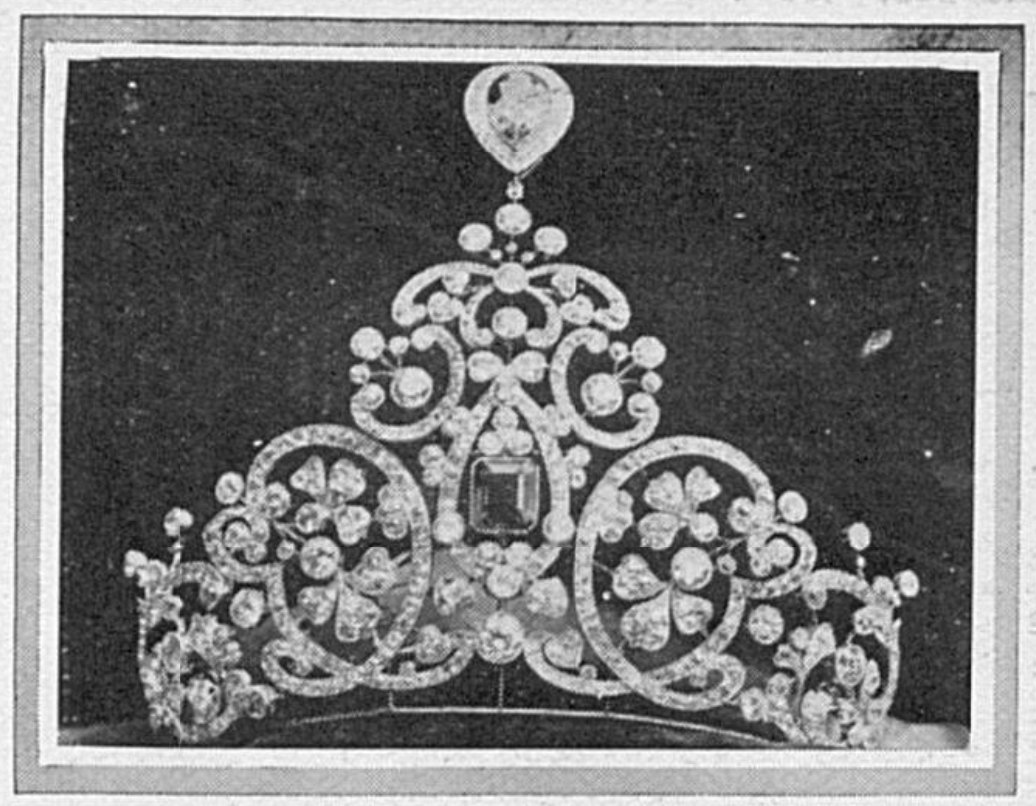

And, in recognition of her wartime service with their organization, 50,000 members of the Voluntary Aid Detachment presented this diamond and emerald tiara to the princess. I haven’t seen a photograph of Mary wearing this tiara. Made by Hunt & Roskell, the jewel was versatile. The side sections of the tiara could be detached, and the central portion flipped over for use as a brooch.

Some have speculated that Mary’s impressive diamond scroll tiara may also have been one of her wedding presents, but I’ve never seen that confirmed. She’s wearing it here at the 1937 coronation, along with the sapphire necklace that was one of her wedding gifts. The large sapphire and diamond element worn here in the center of the tiara was one of her wedding presents as well, a gift from Queen Mary.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.