Today marks the 122nd anniversary of the birth of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, one of the most important royal figures of the 20th century. To celebrate, we’re devoting the month of August to a survey of her most important private jewelry collection: the Greville Bequest. But first, today we’re looking at the unlikely friendship between Dame Margaret Greville and the royal family, and the way that the jewels made their way from Polesden Lacey to Buckingham Palace.

In 1943, in the midst of the Second World War, a black tin trunk embossed with the initials MHG was dispatched from Polesden Lacey, a grand country house in Surrey, to Buckingham Palace. The Queen had been expecting the delivery. Inside the trunk lay a treasure trove of incredible jewels: more than sixty fabulous pieces made by famous jewelry firms like Cartier and Boucheron.

To this day, we only know details about a fraction of the jewel pieces that arrived inside that trunk. But how the jewels got to the palace—and the interesting royal friendship that led them there—is a crucial part of understanding why the Greville Bequest continues to fascinate royal jewelry lovers to this day.

Dame Margaret Greville, better known to many in London social circles as Mrs. Ronnie Greville, was one of the leading hostesses of her generation. Kings and queens, statesmen and celebrities, everyone who was anyone was on the guest list for parties at her Mayfair home on Charles Street and weekends away at her country home, Polesden Lacey. But Maggie’s story began somewhere much less posh, and in much more perilous circumstances.

Margaret Helen Anderson was born in Scotland in 1863. The parents listed on her birth record were William Anderson, a porter working for the Fountain Brewery in Edinburgh, and his wife, Helen, who worked as a cook. But it seems that William Anderson wasn’t Margaret’s father at all. Her mother had a longstanding relationship with William McEwan, owner of the brewery where William Anderson was employed. When Anderson died in 1885, William McEwan and Helen were married. After their wedding, Margaret was often referred to as McEwan’s “stepdaughter,” but it seems to have been an open secret that she was his biological daughter.

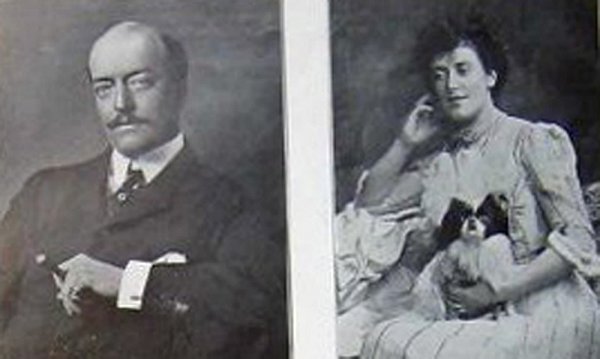

William McEwan’s brewing enterprise made him immensely rich. That wealth translated to political power as well. He was elected as Edinburgh Central’s parliamentary representative in 1886, a seat he held until 1900. In 1907, King Edward VII appointed McEwan as a member of the Privy Council. His rise in the social world also allowed him to secure an aristocratic husband for his daughter. In April 1891, Maggie married the Hon. Ronald Greville, eldest son of the 2nd Baron Greville and officer in the Life Guards. The new Mrs. Greville received a haul of glittering wedding presents, including a diamond tiara gifted by her father, described in the Truth as “composed of three diamond rivières of single stones.”

Ronnie Greville would eventually retire from the army as a captain and seek his own political career. He was elected MP for Bradford East in 1896, though he was often laid low with various illnesses. Meanwhile, Maggie focused on shoring up her position in the social whirl of London. She and her mother were frequently invited to gala events, including state occasions attended by the royal family. Just a few months after Maggie’s wedding, for example, she wore her new diamond tiara to a state opera performance given in honor of the visiting Emperor and Empress of Germany.

Over the years, Maggie found herself drawn closer and closer to London’s most fashionable set. She was presented at court shortly after her wedding, and she began to host small parties at the London home in Charles Street that had been purchased by her father. After Queen Victoria’s death in 1901, Maggie became part of the social circle surrounding King Edward VII. She was a close friend of Alice Keppel, who had a well-documented relationship with the monarch. Maggie’s personality made her just the kind of woman that the king liked to have surrounding him at social events. In 1906, the Westminster Gazette noted, “Young, bright, a capital linguist, a good hand at bridge, and always one of the best-dressed women in Society, Mrs. Greville has speedily become a familiar figure in the little circle specially honoured with King Edward’s friendship.”

For several years, the Grevilles leased Reigate Priory, a Tudor mansion in Surrey, and King Edward made visits there for several consecutive summers during his reign. In 1907, while documenting one of those royal visits, the Graphic called the Grevilles “très répandus in the best and most amusing social world.” The same year, William McEwan acquired Polesden Lacey, a country estate not far from Reigate, for his daughter and son-in-law. But sadly, Ronnie and Maggie’s partnership ended far too soon. In the spring of 1908, just before their seventeenth wedding anniversary, Ronnie was diagnosed with cancer. He underwent surgery to remove a tumor from his larynx that March, but soon afterward, he contracted pneumonia and died.

Maggie went into mourning for a year, escaping England to travel abroad. Devoted to travel as a pursuit, Maggie would traverse the globe during her long widowhood. But back at home, she was also able to maintain her place in royal society. King Edward VII and friends like Mrs. Keppel continued to visit her for weekends at Polesden Lacey. She was also a close friend of his sister, Princess Beatrice, and of Beatrice’s daughter, Queen Ena of Spain. Maggie maintained her connections to the royals after Edward VII’s death in 1910, developing enduring friendships with King George V and Queen Mary and their children. In January 1922, George V made her a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire.

Mrs. Greville’s home near Berkeley Square was often crowded with members of the family for late parties and dances after palace functions. Following a state banquet during a visit from the King and Queen of Italy in 1924, the house’s ballroom was crowded with both Italian and British royals. “Mariegold in Society,” a gossip column published in the Sketch, recounted a humorous moment on the crowded staircase that led to the ballroom during that particular party: “The poor Prince of Wales, unnoticed and unrecognised in the crush, tried for about ten minutes to get up the staircase, but was stuck halfway, where he could neither go up nor down! A footman appeared saying, ‘Make way for the Duke and Duchess of York.’ ‘Don’t bother about me,’ said the Prince rather plaintively from his place in the crush.”

The Duke and Duchess of York, later King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, were particular favorites of Maggie’s. Because Bertie was the second son and never expected to inherit the throne, Maggie decided in 1914 that she would bequeath Polesden Lacey to him on her eventual death. (According to Pam Burbidge, the offer was reportedly made as a recognition of her gratitude toward the late Edward VII for his enduring friendship.) She loaned the house to the Yorks for their honeymoon in 1923, and they were frequent weekend visitors there, especially in the years before their unexpected accession in 1936. Maggie often referred to Elizabeth as the daughter she never had.

Following the outbreak of World War II, Maggie took up residence in the Dorchester Hotel in London. In her waning years, she had flirted with support of the German cause before apparently coming to her senses and throwing her heart and resources behind her home country’s war effort. Her health declined, and she was confined to a wheelchair, but she continued to host parties whenever she could, still dripping in her famous jewels. She died in September 1942, not long after the shocking death of the Duke of Kent. Her visit to Balmoral not long after his death was her final visit with the Queen, who recorded in a letter to a friend that she was “very shocked and sad at the change” in Maggie. A few weeks later, after Maggie’s death, Elizabeth wrote, “I shall miss her very much indeed,” adding that “she was so shrewd, so kind, so amusingly unkind, so sharp, so fun, so naughty.”

In death, Maggie dealt a pair of surprises to the King and Queen. In an unexplained change of heart, she had altered her will and bequeathed Polesden Lacey not to George VI, as originally intended, but to the National Trust. Pam Burbidge notes that Maggie left no explanation behind to clarify her decision, but it seems possible that Bertie’s accession to the throne (and the properties that came with it) was a major factor. I don’t believe Bertie’s reaction to the change in plans has been recorded, but considering the moment in time, he was likely much more preoccupied by other matters. The Trust continues to own and maintain the estate today, and it’s open to visitors. The house is one of the most-visited properties in the Trust’s care.

The second surprise was a more pleasant one. Dame Maggie had bequeathed her famous collection of jewelry to Elizabeth. On September 30, 1942, Elizabeth wrote to Arthur Penn, her treasurer, thanking him for sending along details about the surprise legacy, adding that she “hope[d] to keep it quiet.” But she couldn’t resist sharing the news with the one person who would be most thrilled about the bequest: her mother-in-law, Queen Mary. “I must tell you that Mrs Greville has left me her jewels,” she wrote in October 1942. “She has left them to me ‘with her loving thoughts,’ dear old thing, and I feel very touched, I don’t suppose I shall see what they consist of for a long time, owing to the slowness of lawyers & death duties etc, but it is rather exciting to be left something, and I do admire beautiful stones with all my heart.” (Queen Mary replied a few days later: “I can understand your pleasure about the jewels.” She added, “I never had any such luck—but I am not really jealous.”)

Elizabeth’s hopes to keep the bequest quiet in the midst of war were firmly dashed by January 1943, after the estate went through probate. Newspapers across the country revealed that Maggie “left:—’With my loving thoughts’ all jewels and jewellery to HM Queen Elizabeth.” They clarified, “Dame Margaret Greville, better known as Mrs ‘Ronnie’ Greville, had a jewel collection of considerable value, containing some magnificent pieces. These jewels will belong to the Queen as her private property and will be entirely distinct from the State jewels which she wears as Queen.” (They also revealed that Maggie had left £20,000 to Princess Margaret and £12,500 to Queen Ena of Spain.) But the royal family has still worked to maintain as much privacy as possible around the jewels, not discussing them extensively in public, especially during the years of war and austerity.

When the jewels were delivered to Queen Elizabeth in 1943, they arrived in the same black tin trunk that Maggie had used to store them at Polesden Lacey. The trunk still bore her initials, MHG. To this day, no full inventory of the jewels in that trunk has been published, likely because they are indeed private property, belonging first to Elizabeth and then to her daughter, the present Queen. This has naturally led to (unconfirmed) speculation, including rumors that jewels owned by Marie Antoinette and Empress Joséphine are among the cache. Over the years, the Royal Collection has shared the confirmed Greville provenance of several prominent royal jewels, and on several days over the course of the rest of the month, we’ll be focusing on each of those pieces individually. Stay tuned: there’s lots of Greville sparkle on the way!

For further reading about Dame Margaret Greville, I’d recommend Queen Bees: Six Brilliant and Extraordinary Society Hostesses Between the Wars by Sîan Evans. The Queen Mother’s excerpted letters, edited by William Shawcross, are found in Counting One’s Blessings. Huge thanks also must be offered to Pam Burbidge, a guide, researcher, and historian who volunteers with the National Trust at Polesden Lacey. She kindly sent me a copy of her new book on Dame Maggie, The Maggie Greville Story, which is clearly a labor of love and offers a wealth of information about the famous hostess. The book is currently available for purchase in the UK, but can be delivered internationally from various outlets.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.