It’s October, which means it’s officially the season for telling tales of ghosts, haunted houses, and all manner of scary things. In the historical world of royal jewels, there has been plenty of horror, and I’ll be sharing scary stories of tiara terror every Monday for the rest of the month in the lead-up to Halloween. First up: the chilling story of the debut of La Buena—the “good” Spanish royal tiara that witnessed a horrific scene during its first public appearance.

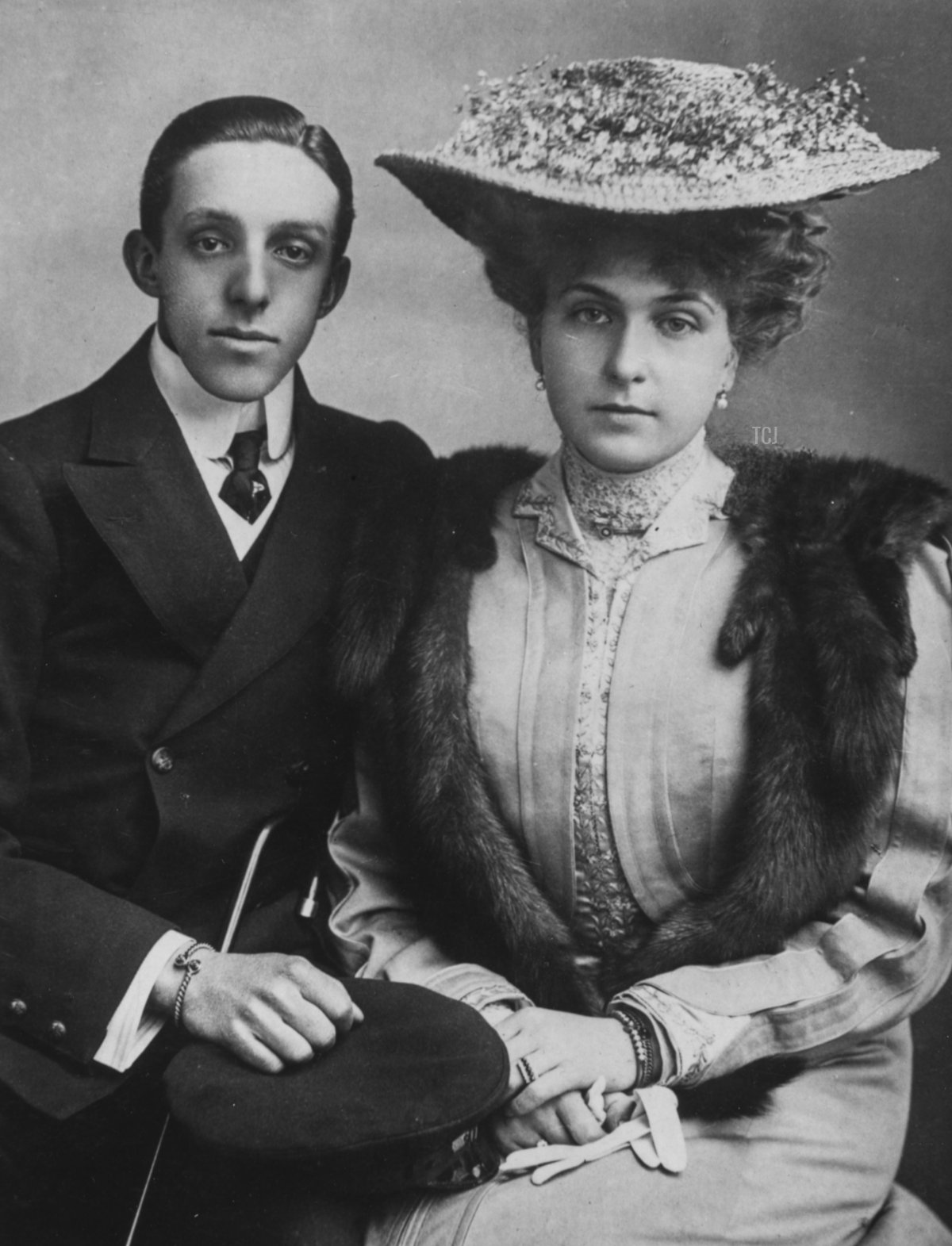

The year was 1905. King Edward VII of the United Kingdom was hosting a grand state banquet that June at Buckingham Palace in London for King Alfonso XIII of Spain. Alfonso, then just 19 years old, was the rare person who had literally been born a monarch: his father, King Alfonso XII, had died before his birth, and baby Alfonso had succeeded to the throne at the moment he took his first breath. By the spring of 1905, the young monarch was searching for a consort. In the ballroom at Buckingham Palace, he laid eyes on King Edward’s 17-year-old niece, Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg. The blond princess, known by her fourth name, Ena, was smitten as well.

The young royals began an epistolary courtship. The romance between them developed swiftly, but a trio of concerns nearly derailed the relationship before it could even begin. The first was a matter of religion: Alfonso was Catholic, and Ena was Anglican. She would have to agree to convert to marry him, a move that would cut her off from her own family’s line of succession. The second was a question of eligibility: Ena’s late father, Prince Henry of Battenberg, was the product of an unequal marriage, something that deeply concerned Alfonso’s mother, Queen Maria Cristina. (Prince Henry’s father was a prince, but his mother was a countess who had been a lady-in-waiting at court before their wedding.)

The third was a major medical issue: Ena’s brother, Prince Leopold, had hemophilia, and there were concerns that she might also be a carrier of the disease, which she could potentially pass on to her children. While the first two concerns were handled—Ena converted to Catholicism, and King Edward upgraded her to the style of Her Royal Highness—the third was mostly brushed aside by Alfonso. But it would prove to be the most serious of all in the long term. Interestingly, there doesn’t seem to have been much discussion about the dangers posed to Ena by the marriage. Just a few days before Alfonso’s state visit to London, he had narrowly escaped an assassination attempt in Paris. A bomb, thrown by an anarchist, exploded but missed the young king’s carriage.

With the prospect of inherited diseases and assassination attempts shrugged off, the couple’s relationship bloomed in the south of France, when they reunited at a villa in Biarritz owned by a cousin, Princess Frederica of Hanover. Afterward, Alfonso took Ena to Spain to meet his mother. Ena’s conversion quickly followed, as did an official diplomatic treaty between the United Kingdom and Spain. Ena turned 18 in April, and a few weeks later, she traveled to Madrid with her mother and brothers for her royal wedding.

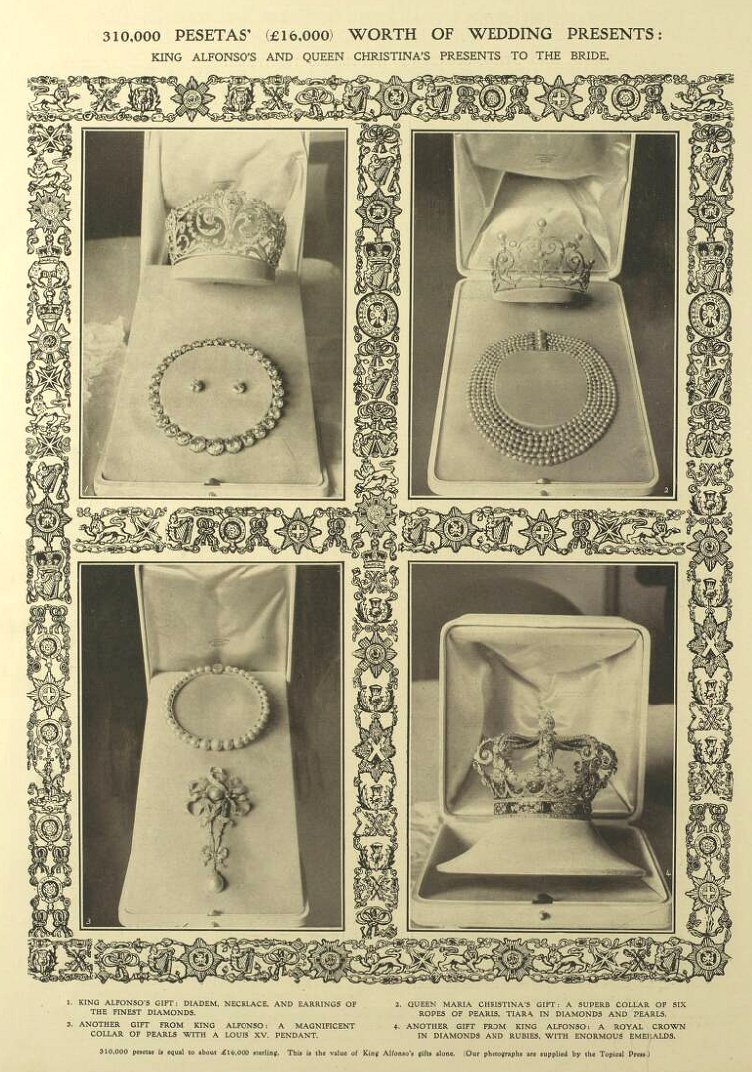

The queen-to-be was greeted at the Royal Palace in Madrid by a treasure trove of wedding presents, including a collection of jewelry that was definitely fit for a queen. Bejeweled gifts had arrived from the bride’s mother, her aunt and uncle, and her future mother-in-law, but it was Alfonso who gave her the greatest cache of jewels. He presented her with an actual crown, as well as necklaces of pearls and diamonds, earrings, and brooches. The star piece of jewelry, however, was a grand diamond tiara, featuring the symbol of the House of Borbón, the fleur-de-lis, rendered in brilliant gems. It’s pictured in its case in the top left of the image above. The diadem had been made by Ansorena, the famed court jeweler of the Spanish royal family. The tiara would be nicknamed “La Buena,” which means the “good one.”

Princess Ena wore the tiara in public for the first time on May 31, 1906, for her royal wedding. The jewel crowned an ensemble that also included a white brocade gown, another gift from Alfonso, that was decorated with silver embroidery and Spanish lace and trimmed with orange blossoms. The lace veil that Ena wore was a gift from her mother-in-law, Queen Maria Cristina, who had worn the same veil for her own royal wedding in 1879. Her additional jewels included a diamond necklace (a gift from Alfonso), pearl earrings, a brooch with a pendant pearl (also a gift from Alfonso), and several bracelets, including one gifted by members of the Spanish royal family. Fully attired in her bridal finery, Ena stepped into the Mahogany State Coach with her mother, Princess Beatrice, and Queen Maria Cristina for the journey to the Royal Monastery of San Jerónimo for the ceremony.

King Alfonso XIII was waiting at the church for his bride, also attired in his finest clothing, including white satin breeches and special gold spurs. The bridal procession took its time to arrive at the church, chosen as the location for the ceremony in part because it provided a lengthy five-mile carriage route along which the people of Madrid could gather to see the new Queen of Spain on her wedding day. It was a warm day, and all along the route, people cheered mightily as the princess waved from her carriage—though, based on a recommendation from security officials, they were asked not to throw flowers at the carriages as they drove past. Alfonso grew antsy and sent a message asking the procession to pick up the pace, but he still waited at the church for an entire hour for his bride to arrive.

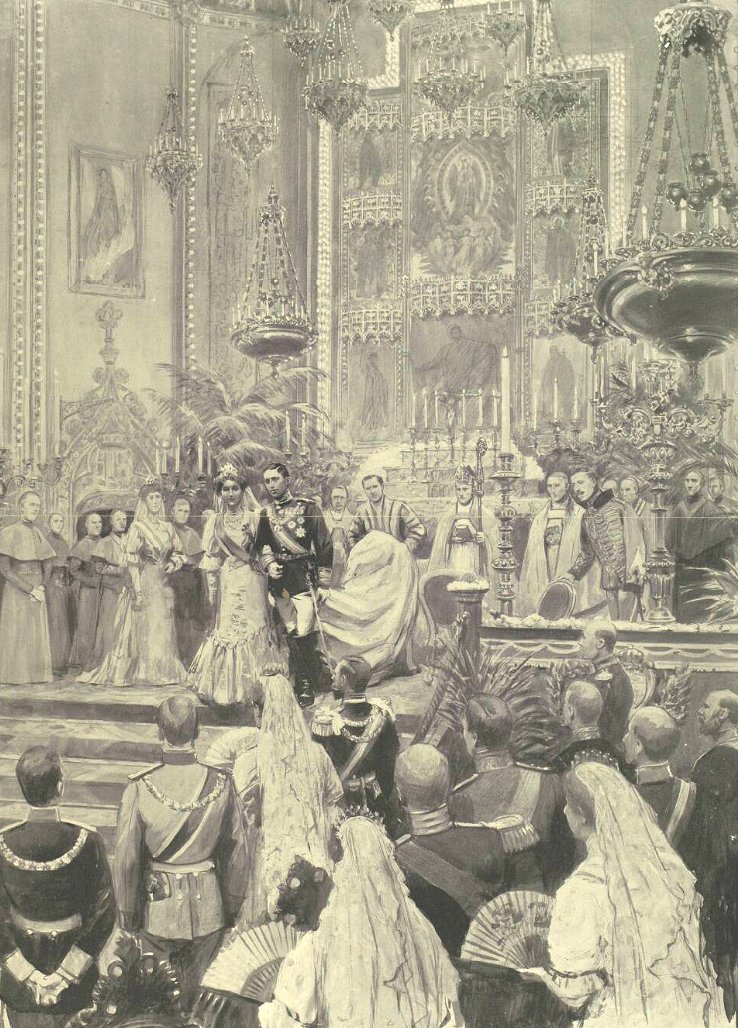

When she stepped out of the carriage, gleaming in white and sparkling in diamonds and pearls, Ena would have been an impressive sight. The other royal ladies in attendance—including the Princess of Wales (Queen Mary), the Duchess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and Grand Duchess Vladimir of Russia—were also wearing tiaras, adding to the grandeur of the scene. Inside the church, the wedding ceremony proceeded flawlessly. A choir of 200 sang voices sang hymns as the royals stood before an altar decorated with candles and roses. The Archbishop of Toledo, Cardinal Sancha, pronounced the couple married, and transformed Her Royal Highness Princess Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg into Her Majesty The Queen of Spain in the process.

The jubilant couple and their families spilled out of the church and back into the sunshine, where a cacophony of church bells rang out as cannons fired in celebration. Alfonso and Ena climbed into the the crown coach at the head of a remarkable royal procession. They were immediately followed by a gold-paneled coach, left empty per tradition, and then by more than fifteen carriages and coaches containing royal dignitaries and family members. Once the glittering assemblage was seated inside their vehicles, the procession set off through the streets, drawn by magnificent horses.

Well-wishers shouted congratulations to the couple from the street and from the windows and balconies of buildings along the route as the carriages made their way back to the Royal Palace. The procession had made its way along the Calle Mayor, one of Madrid’s main thoroughfares, and had nearly reached the palace complex when, suddenly, a single bouquet of flowers floated down from the third-floor balcony of Number 88, a building of flats beside the Italian embassy. And then, the street exploded into chaos: first, a blinding flash of light, and then a reverberating crash of sound. Fragments of metal and clouds of smoke and debris enveloped the procession, and the carriages teetered as the horses panicked in the melee.

The bouquet had concealed a bomb, hurled by an anarchist and aimed squarely at the coach carrying Alfonso and Ena. The explosive device narrowly missed the carriage somehow—deflecting off an electric wire, according to some witnesses. The bomb landed among the horses pulling the coach, killing some of them instantly. Several more victims were killed who had been cheering from the other balconies on the building. In the chaos, some believed that the King and Queen had been killed. But while there were numerous tragic casualties among the onlookers, both Ena and Alfonso somehow emerged physically unscathed.

Alfonso was seething with anger as he stepped down from the coach. A reporter for the Daily Telegraph reported that he shouted, “This is infamous. It is cowardice. If they wish to kill me, let them meet me face to face, without shedding innocent blood,” and pointed at the balcony from which the bomb had been thrown. (The perpetrator, a man named Mateu Morral, was killed a few days later.) The toll on the innocent bystanders was indeed immense. Though the royals had escaped, more than 20 were killed and more than 100 more were injured. In the days after the wedding, Alfonso would spend a great deal of time visiting the wounded and viewing the bodies of the dead, praying alongside those who had been injured.

Alfonso reportedly tried to shield Ena’s face from the carnage that surrounded them as she was helped out of the carriage, her diamond wedding tiara still sparkling atop her head. Both of their clothes were streaked with the blood of those around them who had been injured in the blast. A piece of shrapnel had reportedly shattered the window of the coach and struck Alfonso’s shoulder, damaging one of the links of the collar of the Order of the Golden Fleece. The second carriage, the one that was traditionally kept empty, was pulled forward so that the King and Queen could use it for the remainder of the drive to the palace.

As they prepared to set off, they were surrounded by members of the British diplomatic party, including the British ambassador, that had traveled from London to attend the wedding. They walked alongside the carriage as an informal protective escort party for the rest of the short journey. “It may be imagined with what feelings the Queen saw the faces of old friends and the uniforms of the old country,” a correspondent from the Times reflected. Among the party were members of the Cochrane family, who had been close companions to Princess Beatrice and her children for years. Ena later confided in Minnie Cochrane, Beatrice’s lady-in-waiting, that she had been very comforted to see Minnie’s brother walking beside her following the incident.

Inside the palace, the King and Queen were immediately surrounded by their families and friends. Queen Ena, composed on the surface, was clearly in shock, repeating the phrase “I saw a man without any legs” over and over as others attempted to soothe her. Rumors immediately began to fly about the intended target of the bombing. Early on, some presumed that the explosive must have been meant for Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich of Russia, the uncle of the reigning tsar. After all, Vladimir’s father, Tsar Alexander II, had been assassinated in similar circumstances in 1881, and his brother, Grand Duke Sergei, had been killed when a bomb was thrown at his carriage in Moscow in February 1905. During the somber wedding reception held at the palace in the aftermath, during which no one felt able to eat, the Duchess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha—daughter of Tsar Alexander II and sister of Grand Dukes Vladimir and Sergei—was overheard sighing languidly, “I’m so very accustomed to these sorts of things.”

But it quickly became clear that the bomb had always been meant for Alfonso. The wedding had been held exactly a year to the day after the failed attempt on Alfonso’s life in Paris, and it was said that several warnings had been issued about possible further attempts in coordination with the wedding celebrations. Sadly, the warnings may have been dismissed in part because these attempts were increasingly commonplace at the time. This attempt would indeed be far from the last experienced by this particular group of illustrious royals. The crowd that had gathered around Alfonso and Ena as they arrived at the palace, shaken but alive, included Prince Luis Filipe, heir to the throne of Portugal, and Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Habsburg thrones—both of whom were subsequently murdered in their vehicles while traveling through Lisbon and Sarajevo.

It was far from an auspicious beginning for Ena and Alfonso. The couple had seven children together, but their family life was marred by Alfonso’s infidelities and by the hemophilia that Ena did end up passing along to two of their sons. Alfonso lost his throne in 1931, and the couple separated in exile. Ena purchased a home in Switzerland, where she lived for much of the rest of her life. She remained the matriarch of the exiled family, and eventually—though she didn’t live long enough to see it—her grandson, King Juan Carlos, was restored to the throne. She left the current royal family a fabulous gift in the form of a jewelry bequest, the joyas de pasar, worn by the reigning queen or queen consort in Spain. The collection includes La Buena, the tiara that endured such a terrifying debut in 1906. Today, the magnificent diadem is worn on grand occasions by Queen Letizia, the wife of Ena’s great-grandson, King Felipe VI of Spain.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.