The third installment in our Halloween-themed series of chilling royal jewelry stories continues today with the story of a shipwreck in Morocco—and the British royal jewelry that never emerged from the waters below.

The year was 1911. It had been a year full of grief and celebration for the British royal family, who mourned the loss of King Edward VII in May 1910 and celebrated the coronation of his son and successor, King George V, in June 1911. The new monarch had three sisters: Princess Victoria, who lived as a companion to their mother, Queen Alexandra; Queen Maud, the wife of King Haakon VII of Norway; and Princess Louise, who held the title of Princess Royal.

Known to be quiet and shy, Princess Louise had married Alexander Duff, a much-older friend of her father, at the age of twenty-two. Her grandmother, Queen Victoria, had elevated him from an earldom to the title of Duke of Fife. Though Louise remained close to her royal family, and occasionally took part in royal engagements, she settled down into a fairly private married life. She gave birth in quick succession to a son (who did not survive) and two daughters (who both did). Alexandra and Maud, her daughters, were given the title of princess and the style of highness by their grandfather, King Edward VII, in 1905. Both princesses were considered to be extremely eligible royal bachelorettes as they came of age, with the younger of the two, Princess Maud, making her formal debut at court in 1911. Even so, they often found themselves outside of the whirl of London society. The family’s primary residence was at Mar Lodge in Scotland, and the Duke and his trio of princesses were also frequent travelers abroad.

In December 1911, the Fife family—62-year-old Alexander, 44-year-old Louise, 20-year-old Alexandra, and 18-year-old Maud—packed their trunks for a journey that would take them away from the chilly British winter to the warm sands of Egypt. It was a trip they were all familiar with, having made the same trek during previous years. The three-month retreat to a less-harsh climate was a fashionable one for many Edwardian royals and aristocrats, and it was thought to have health benefits as well. Louise in particular was described in the press at times as having “a very nervous state of health” and a growing dislike for public appearances.

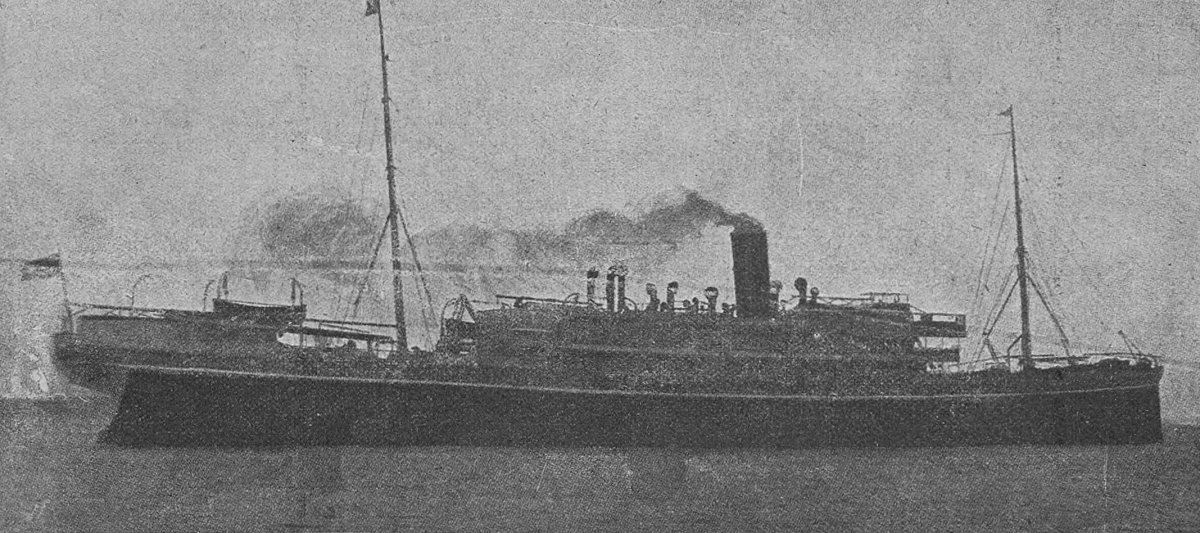

On Friday, December 8, 1911, the family of four boarded a Peninsular & Orient Line steamer, the SS Delhi, at Tilbury in Essex, bound for Port Said in Egypt, where the Fifes would disembark. The name of the ship must have seemed like a very good omen at the time. Halfway around the world in India, Louise’s brother and sister-in-law, King George V and Queen Mary, had just arrived for the immense Delhi Durbar coronation festivities, which would take place on December 12.

Just hours after the imperial festivities had begun in Delhi, however, the SS Delhi was in distress. At one o’clock in the morning on Wednesday, December 13, the steamer encountered heavy fog and choppy seas at the entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar. Shortly afterward, the liner ran aground near Cape Spartel on the Moroccan coast. Contemporary news reports describe the frightening scene experienced by the hundred passengers on board the ship: “The conditions were terrible. The night was black and stormy, with strong westerly winds and torrential rains. Immediately the vessel struck, the call, ‘All on deck,’ was heard above the raging of the wind and water, and in a very short time the passengers, including the Royal party, clad in their night attire, over which great coats had hastily been donned, were gathered in the deck saloons. Lifebelts were served out to all.”

The ship listed badly to one side after striking the coast. With water rushing in to the lower cabins, waves also began to break heavily over the deck, giving the sensation that the ship was being dragged closer and closer to the rocky shore. Distress calls were cabled to Gibraltar and Tangiers, and a trio of naval warships were sent out to aid the grounded steamer. But the weather continued to be a problem. At one point, a lull in the storm convinced the crews of the ships to try to sending a launch from the French ship, the Friant, to transfer some of the women and children from the Delhi to one of the other British ships, the HMS Duke of Edinburgh. But soon after the successful transfer, the weather suddenly began to rage again. After brief hesitation, the launch was sent back for another load of passengers, and this time around, the operation became much more perilous. An enormous wave swept over the smaller boat, washing a crew member overboard. Even so, after the passengers were loaded on to the British ship, the launch was sent back a third time. Before the boat could even reach the Delhi, though, it was capsized in the heavy seas. Three of the French crew members aboard the launch drowned.

Throughout these initial rescue attempts, the Fife family remained huddled on board the Delhi for more than nine hours. Following the tragic accident aboard the launch, the crew decided that it was too dangerous to try to transfer the royal party directly to another ship. They should be ferried straight to the coast, they concluded. Still wearing their pajamas, covered by heavy coats and life jackets, the four would be removed from the Delhi and placed aboard a launch belonging to the Duke of Edinburgh, which would then carry them to shore. Princess Louise was clutching a case containing her jewelry. Though another member of the party had offered to carry it for her, she insisted on holding the jewel case herself.

The royals were accompanied in this perilous journey by a familiar face: Rear-Admiral Christopher Cradock, second in command of the Atlantic Fleet, who had responded to the wreck of the Delhi with the two British warships. Cradock was close to the royal family, having served aboard the royal yacht Victoria & Albert and as a naval aide-de-camp to King Edward VII and King George V. But even Cradock’s reassuring presence couldn’t make the journey ashore easy. Newspapers wrote that the members of the royal party (which also included the family doctor) experienced “very considerable difficulty” as they tried to get into the British launch, “and the ladies had literally to be dropped and caught.” As the boat headed to shore, the enormous waves began to overwhelm the small vessel. The men aboard, including the Duke, began to try to bail out water, but to no avail. Before reaching the shore the boat was swamped and sank, sending all of her passengers into the water. Princess Louise’s jewel case was swept out of her hands. Much worse, Alexandra disappeared briefly below the surface of the water and had to be rescued by a sailor and another passenger. Soaked to the skin, with heavy rain still falling, the entire family eventually stumbled on to the beach, trudging across the wet sand and rocks in their bare feet.

Already exhausted from the ordeal, the Fifes made their way to the lighthouse at Cape Spartel, where they were finally able to take refuge from the rain. There, they were given a change of clothing and warmed with hot tea beside the fire. Still clad in his nightshirt, and wearing a pair of trousers borrowed from the keeper of the lighthouse, the Duke of Fife made plans for the family to proceed to the diplomatic legation at Tangiers. But that trek would be yet another uncomfortable journey. A reporter with the Times wrote, “It was after six o’clock last evening when the Princess Royal, the Duke of Fife, and the two Princesses, drenched with rain, arrived on muleback, guided by the glimmer of a few native lanterns, at the British Legation, where every preparation had been made for their reception. Their luggage remains on board the Delhi, and they have no clothes except the lighthouse keeper’s garments in which they made the journey from Cape Spartel.” By all accounts, the entire Fife family handled the ordeal with exceptional “coolness and pluck,” and Princess Louise had enough energy to send a simple wireless message—”All safe, Louise”—to her worried mother, Queen Alexandra, before climbing into bed.

In the end, all of the passengers were retrieved safely from the wreck of the Delhi, though the ship itself was a total loss. The three French sailors who had lost their lives in the rescue attempt were remembered by both the British and the French, with a monetary fund dedicated to helping their families. (Queen Alexandra sent a personal message of thanks and condolences to the families as well.) Valuable cargo on board the wrecked ship proved difficult to recover, and Princess Louise’s jewels were never seen again, lost forever in the sea near the Moroccan coast. Reporters noted that her stubborn desire to keep the jewels safe by carrying them with her ultimately led to their demise. “It is said,” wrote one correspondent, “that if the Princess Royal had accepted the advice of those on the Delhi she would not have lost her jewels. An effort was made to induce her to leave them on board, but she insisted on taking them with her in the boat. As they have been buried in moving sands they are unlikely to be recovered.” We don’t know precisely which jewelry pieces were in that case, though the collection definitely didn’t include the Fife Tiara or her Diamond Fringe Tiara, which still exist today.

But sadly, the lingering effects of the shipwreck would cause even more acute sadness for the Fife family in the weeks to come. The family arrived in Port Said aboard a different liner, the Macedonia, on Wednesday, December 27, and made their way to Cairo to begin their three-month winter stay along the Nile. Princess Louise had caught “a chill” from their rainy, wet ordeal in Morocco, but she quickly recovered. The Duke, however, suffered from much more serious lingering effects. On January 23, the family had to cancel a planned engagement in Khartoum as a consequence of his illness.

For several days, Alexander had been feverish and suffering from a pain in his side. He quickly developed pleurisy, and on Monday, January 29, he died at Aswan. Because of a special provision made in 1900 by Queen Victoria, Alexander’s elder daughter, Princess Alexandra, inherited the Fife dukedom on his death. Princess Louise lived for another two decades after her husband’s death. She saw both of her daughters marry and have children of their own. Today, Princess Maud’s descendants hold the Fife dukedom, and Louise’s most glittering surviving jewels are on display at Kensington Palace in London.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.