Our Monday series of tiara horror stories for the month of October continues today with the story of a grand royal tiara from Norway that was stolen in a daring heist in central London. This is the terrible tale of the demise of Queen Maud’s Pearl Tiara.

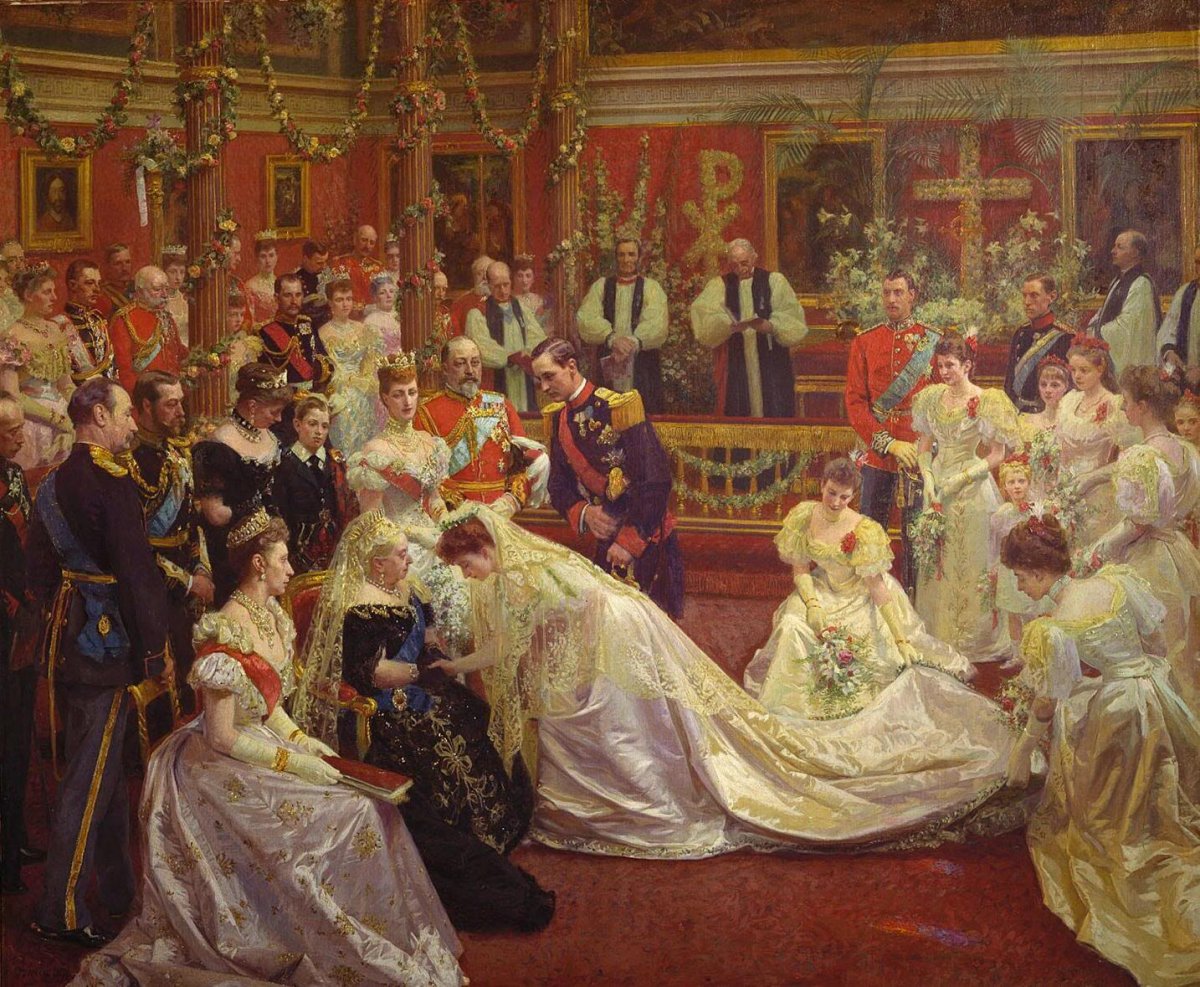

As always, let’s start at the beginning—and, as is so often true, the story begins with a royal wedding. In the summer of 1896, Princess Maud of Wales, the youngest daughter of the Prince and Princess of Wales, married a cousin, Prince Carl of Denmark. The glittering wedding was held in the presence of Maud’s grandmother, Queen Victoria, in the private chapel at Buckingham Palace. Royals from across Europe, most of whom were related to the bride and groom, were crammed into the small space for the wedding.

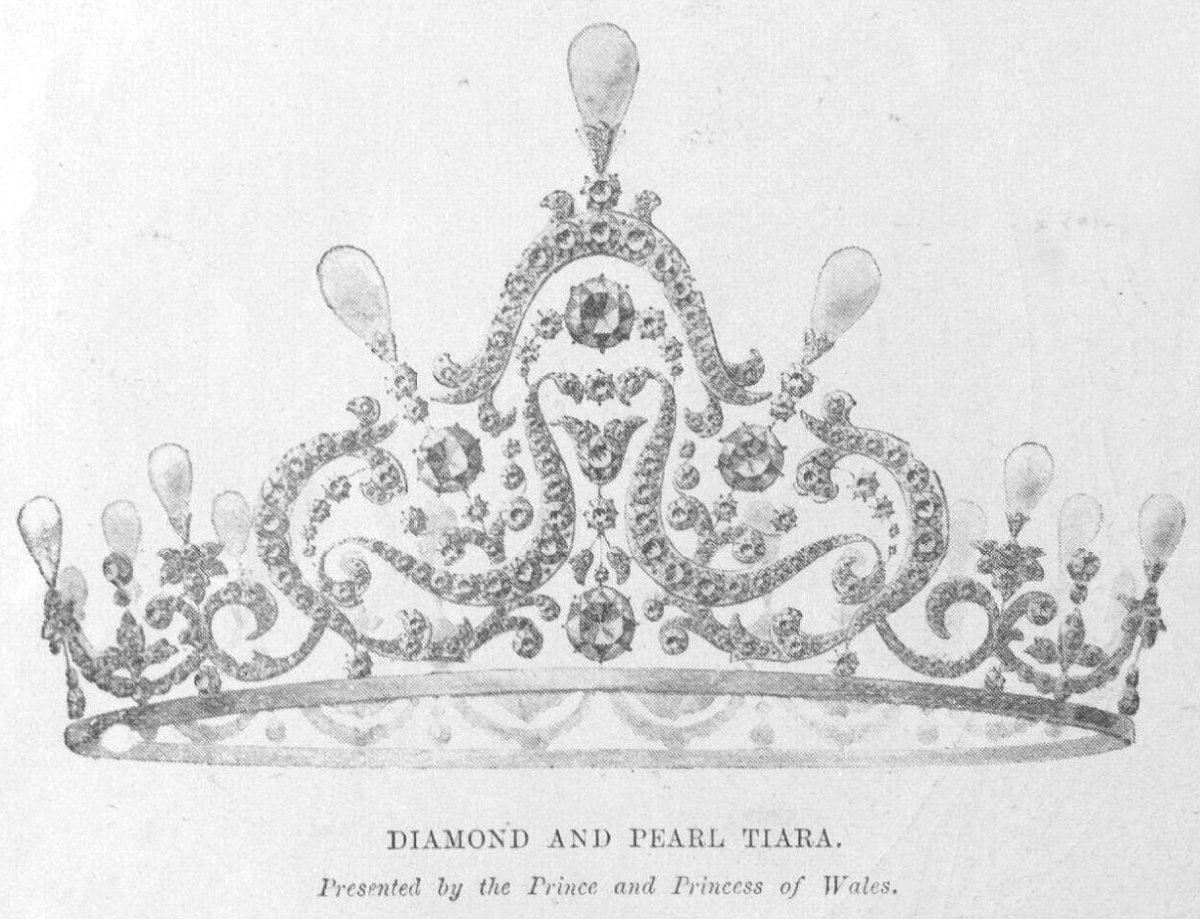

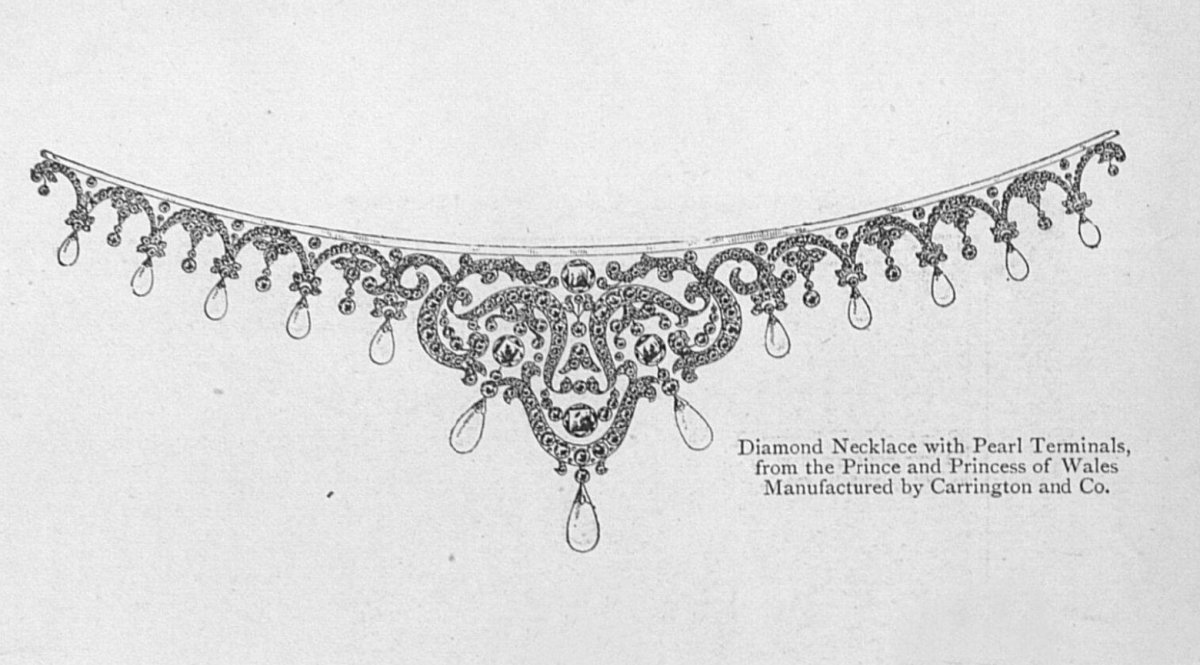

Maud received a treasure trove of wedding presents, including lots of jewels fit for a princess. After all, Maud’s father was the heir to the British throne, and her new father-in-law was heir to the throne of Denmark. There would be plenty of opportunities for her to sparkle in grand jewels at gala occasions in both countries. Accordingly, her parents gave her a diamond and pearl tiara, which was made by Carrington & Co. The jewel, shown in a contemporary newspaper illustration above, featured floral and scroll motifs in its design.

Versatility is always an important factor when considering jewelry gifts for a newly-married princess, too. Her collection is infinitely more useful if the jewels she receives early on can be worn in multiple settings and configurations. As this newspaper illustration shows, the diamond and pearl tiara was also able to be worn as a necklace (and, based on the illustration, presumably as a corsage ornament as well). Even better, the tiara had a second smaller setting as well. The large central scroll element could be removed, and the jewel could then be worn as a small diamond and pearl fringe-style tiara.

For the next several years, Prince Carl and Princess Maud divided their time between Denmark and England, spending significant parts of the year at Appleton, their small house on the Sandringham estate. Their son, Prince Alexander, was born at Appleton in 1903. Prince Carl continued his career in the Danish navy, allowing Maud to continue to spend a good deal of time with her family in Britain. Maud grew closer in proximity to the British throne in 1901 with the death of her grandmother, Queen Victoria, and the accession of her father, King Edward VII.

For King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra’s coronation in August 1902, Maud decided to loan the diamond and pearl tiara to another close member of the family: her beloved sister, Princess Victoria. Toria is pictured here wearing the tiara with her coronation robes during the festivities. Grand banquets and family dinners in both the United Kingdom and Denmark also gave Maud plenty of occasions to wear all of her wedding jewelry, including the versatile diamond and pearl tiara.

But no one could have anticipated an even greater change on the horizon for Maud and Carl. In June 1905, around the time that this photograph was taken, the Norwegian legislature passed a law dissolving the country’s joint union with Sweden, a move confirmed a few months later in a public vote. In October, King Oscar II recognized Norway as an independent state. The people wished to continue a system of government headed by a constitutional monarch, but not one they’d have to share with another nation. They began considering candidates to invite to take over the new independent throne of Norway, and after much discussion, they decided to offer the throne to Prince Carl. He had plenty of family ties that made him an attractive prospect: his father was the Crown Prince of Denmark, his mother was a niece of the King of Sweden, and his father-in-law was the King of the United Kingdom—and little Prince Alexander’s recent birth meant that he already had a son and heir.

On November 18, 1905, the Norwegian parliament elected Prince Carl as the new King of Norway. After securing official permission from his grandfather, King Christian IX of Denmark, Carl accepted the offer. He changed his name, becoming King Haakon VII, a name traditionally used by Norwegian kings, and gave Alexander a new title and name as well: Crown Prince Olav. Maud was now the Queen of Norway, and her collection of wedding gift jewels formed the cornerstone of a brand-new royal jewelry collection.

The tiara remained with Maud for the rest of her life, traveling back and forth with her from Norway to England. In 1938, Maud made one of her usual autumn journeys to England, and she packed her jewelry in her luggage for the trip. In October, she arrived at Appleton to stay for a few weeks before heading to London. While staying in Mayfair, she fell ill, and doctors performed an abdominal operation. Haakon quickly traveled to England to be with her, but he was asleep at Buckingham Palace when she unexpectedly died in the early hours of November 20, 1938, at the age of 68.

With the family deep in grief and focused on returning Maud’s body to Norway for her funeral, the jewelry she had brought with her was an afterthought. Left behind in Britain, the jewels were held at Windsor Castle. Then, with the outbreak of World War II in 1939, everyone’s thoughts were on survival. The jewels were just about as safe as they could be right where they were, and that’s where they stayed for more than a decade. When Crown Prince Olav and his wife, Crown Princess Märtha, came to the United Kingdom for Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation in 1953, they finally retrieved his late mother’s jewelry and brought it back to Oslo.

But Crown Princess Märtha, sadly, didn’t have much time left to use her late mother-in-law’s jewels. She died of cancer in 1954, less than a year after the British coronation. Though Märtha’s personal jewelry was subsequently used by both of her daughters, Princess Ragnhild and Princess Astrid, the family decided to wait to divvy up Queen Maud’s jewelry until Olav and Märtha’s son, Harald, married. Another fourteen years elapsed before Crown Prince Harald wed his longtime love, Sonja Haraldsen, in 1968, and the siblings could make their decisions about the jewels.

Harald and Sonja’s portion of the bejeweled inheritance included the grand diamond and pearl tiara that Maud received as a wedding gift. It quickly became one of Sonja’s favorite pieces, worn during her tenure as Crown Princess of Norway and then, after 1991, as Queen of Norway. Above, she wears the tiara (plus the Drapers’ Company Brooch, another of Maud’s wedding gifts) for a dinner in Oslo aboard the royal yacht Britannia, hosted by Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh, in May 1981. (Elizabeth wears several familiar pieces here as well: the Girls of Great Britain & Ireland Tiara, the Greville Chandelier Earrings, the Diamond Festoon Necklace, and Queen Mary’s Lover’s Knot Brooch.)

And then, in 1995, tragedy struck. The Norwegian royal family sent several pieces of jewelry to Garrard in London to be cleaned. Queen Maud’s Pearl Tiara was one of the jewels that had been sent to Regent Street to be professionally maintained, along with at least two of Queen Sonja’s brooches. The employees at Garrard finished the cleaning process, and on Sunday, February 6, they were preparing to send the jewels back to Norway. A pair of security guards, acting as couriers, arrived at the Regent Street location to pick up the jewels and return with them to Oslo on a flight out of Heathrow.

But the movements of the couriers had apparently been closely tracked. At 10:25 in the morning, as the two arrived at the firm’s headquarters, a trio of thieves were hot on their heels. One of the men, dressed as a police officer, pulled up on a motorcycle. Armed with a gun, he followed the couriers into the shop and convinced guards working on the premises to allow him, plus his two accomplices, inside. The trick worked. The team of robbers bound and gagged the guards, stole their keys, and took possession of the jewels. As the thieves fled with the tiara and four more pieces of jewelry, including Sonja’s brooches and two pieces belonging to Garrard, they reportedly destroyed security video tapes and smashed a camera over the building’s entrance.

Twenty minutes after the thieves had entered the building, a silent alarm inside was triggered. Scotland Yard officers quickly responded, but in the chaos of the moment, there was confusion about precisely what had happened. When police arrived to free the guards, they were told that some of the thieves might still be inside the building—possibly the man who had been carrying a firearm. In response, Commander Tony Rowe authorized a major operation to try to protect the public, sending in several teams of armed Scotland Yard officers and fencing off a four-block radius around Garrard. A six-hour standoff ensued, with officers hustling members of the public away from the area.

Eventually, though, everyone realized that the thieves had gotten away, jewelry in hand. Afterward, Rowe was grilled by journalists about the decision to mount such a disruptive operation in the middle of one of the world’s busiest cities. He stated, “My officers were properly cautious. We could have gone in there, we could have strolled around, we could have come out and said everything was alright. But they still could have been in there hiding.” For Rowe, the extreme caution was more than worth it. “We regret the inconvenience to a lot of people,” he added, “[but] I would be gravely embarrassed if the people had escaped through our lack of interest, lack of awareness or lack of professionalism. I would be gravely embarrassed if a member of the public or one of my police officers got shot because we were careless about what we did.”

Queen Maud’s tiara was never seen again. To atone for the loss, Garrard made a replica version of the original Carrington tiara for the Norwegian royals. That’s the tiara that Queen Sonja still wears regularly today, most recently for the Golden Jubilee celebrations in Denmark. The smaller setting of the tiara has also been worn by Crown Princess Mette-Marit and Princess Märtha Louise. It’s not quite the same as having a century-old tiara in your jewelry box, but given the circumstances of the original tiara’s vanishing act, it’s just about the next best thing.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.