Seventy-five years ago today, one of the most important and enduring royal marriages in history began. Let’s take a look back at the story of the wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip, known best to us as Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh.

On Thursday, November 20, 1947, Princess Elizabeth of the United Kingdom awoke in her private apartments at Buckingham Palace at her usual time: 7:30 in the morning. It was a drizzly, chilly day in London. Both snow and rain had fallen on the throngs of people who had already gathered overnight along the processional route to try to catch a glimpse of the royal family during the celebrations. For 21-year-old Elizabeth, a long-awaited day had finally arrived. More than a year after she’d accepted Prince Philip’s proposal, months after their engagement was officially announced, and days into a lengthy series of pre-wedding festivities, she was finally going to be able to marry her prince.

Elizabeth had had an exhausting few days. Running on little sleep, she helped to entertain foreign relatives, danced at pre-wedding balls, stood still through wedding dress fittings, and rehearsed the grand ceremony at Westminster Abbey. On Wednesday, she had watched as delivery trucks and vans arrived in a flurry at the palace, dropping off her wedding gown (heavily guarded and packaged in a long box) and the six-tier wedding cake. Now, she was able to spend a leisurely morning preparing for the ceremony.

Across London, the groom woke in a different palace. Prince Philip spent his last night as a bachelor at the Kensington Palace apartment of his maternal grandmother, the Dowager Marchioness of Milford Haven. A granddaughter of Queen Victoria, Victoria Milford Haven was one of the members of the extended family who had lost her royal title in the wake of World War I, but she was still very much a part of the royal circle. Victoria was the matriarch of a brood that included Philip’s mother, Princess Andrew of Greece and Denmark, and two more surviving siblings, Crown Princess Louise of Sweden and Lord Mountbatten. The Mountbattens would make up the majority of Philip’s family representatives at the wedding. His father, Prince Andrew, had died three years earlier, and his three surviving sisters were not invited—a post-war diplomatic decision made because they were all married to Germans.

The night before, King George VI had awarded Philip a series of new titles and honors. Several months earlier, before the royal engagement was announced, the Greek prince had renounced his titles and styles, becoming Lieutenant Philip Mountbatten and securing British citizenship. On Wednesday evening, the King had elevated Philip to the title and status of HRH The Duke of Edinburgh, Earl of Merioneth, and Baron Greenwich. He also made Philip a Knight of the Garter, giving the prince a sparkling new star to pin to his naval uniform on his wedding day. The elevation came too late to make changes to the program for the wedding service, which still referred to him as “Lt. Philip Mountbatten.”

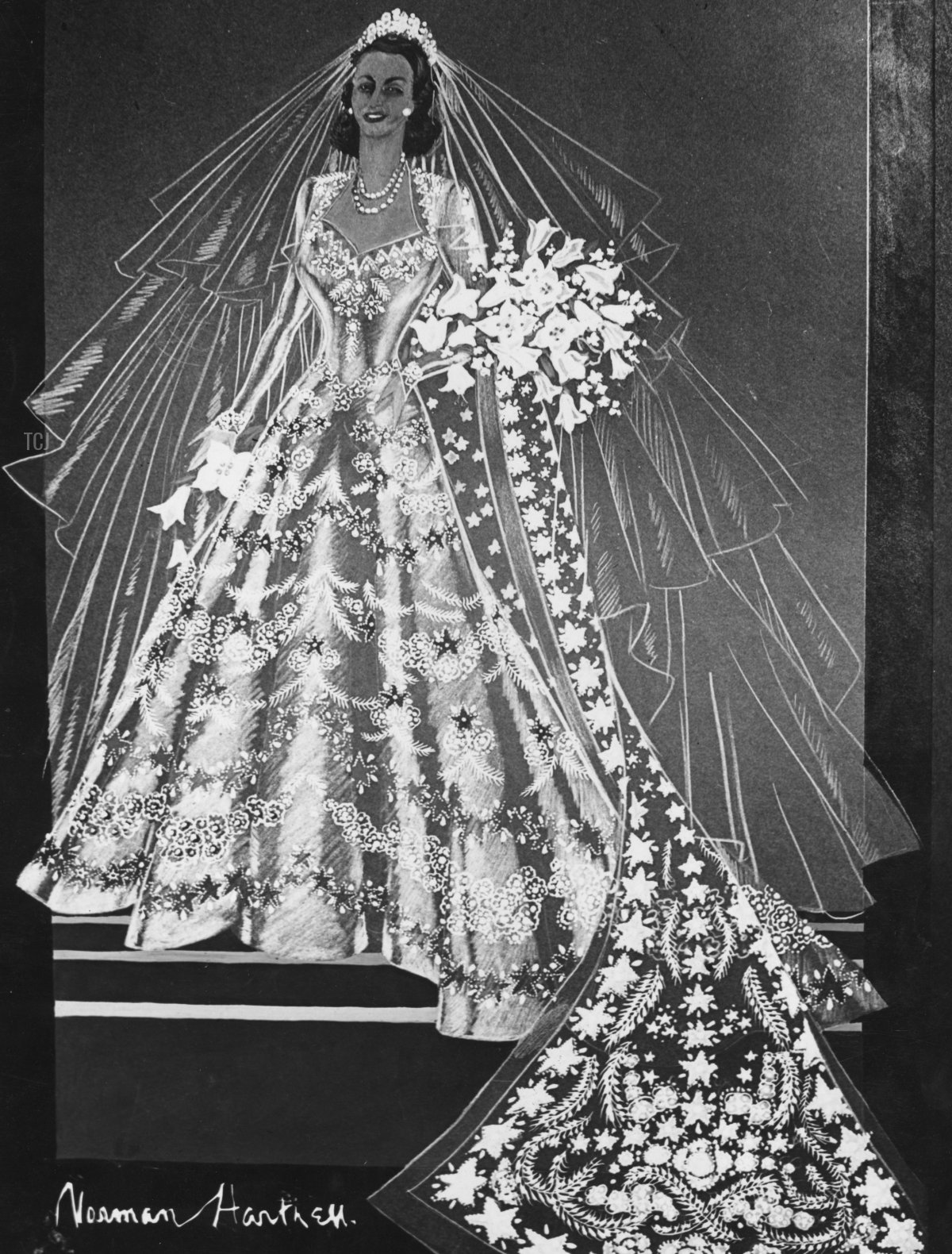

At Buckingham Palace, preparations kicked into high gear as the morning progressed. Elizabeth’s bridal bouquet, made of white orchids with a traditional sprig of myrtle, was delivered to the palace just before nine. Forty-five minutes later, two fitters arrived from Norman Hartnell’s studio to prepare the wedding gown, which had been dispatched to the palace the day before.

The gown, a highly guarded secret, was made of white satin embroidered in pearls and crystals with star lily and orange blossom designs. The dress featured a sweetheart neckline and a lengthy train, and Elizabeth wore a pair of high-heeled satin dress sandals with the ensemble. As the dress was being readied for the bride, Elizabeth carefully applied her own makeup: powder, rouge, and a lipstick in a darker-than-usual shade, designed to be visible to the black-and-white cameras recording the day’s events.

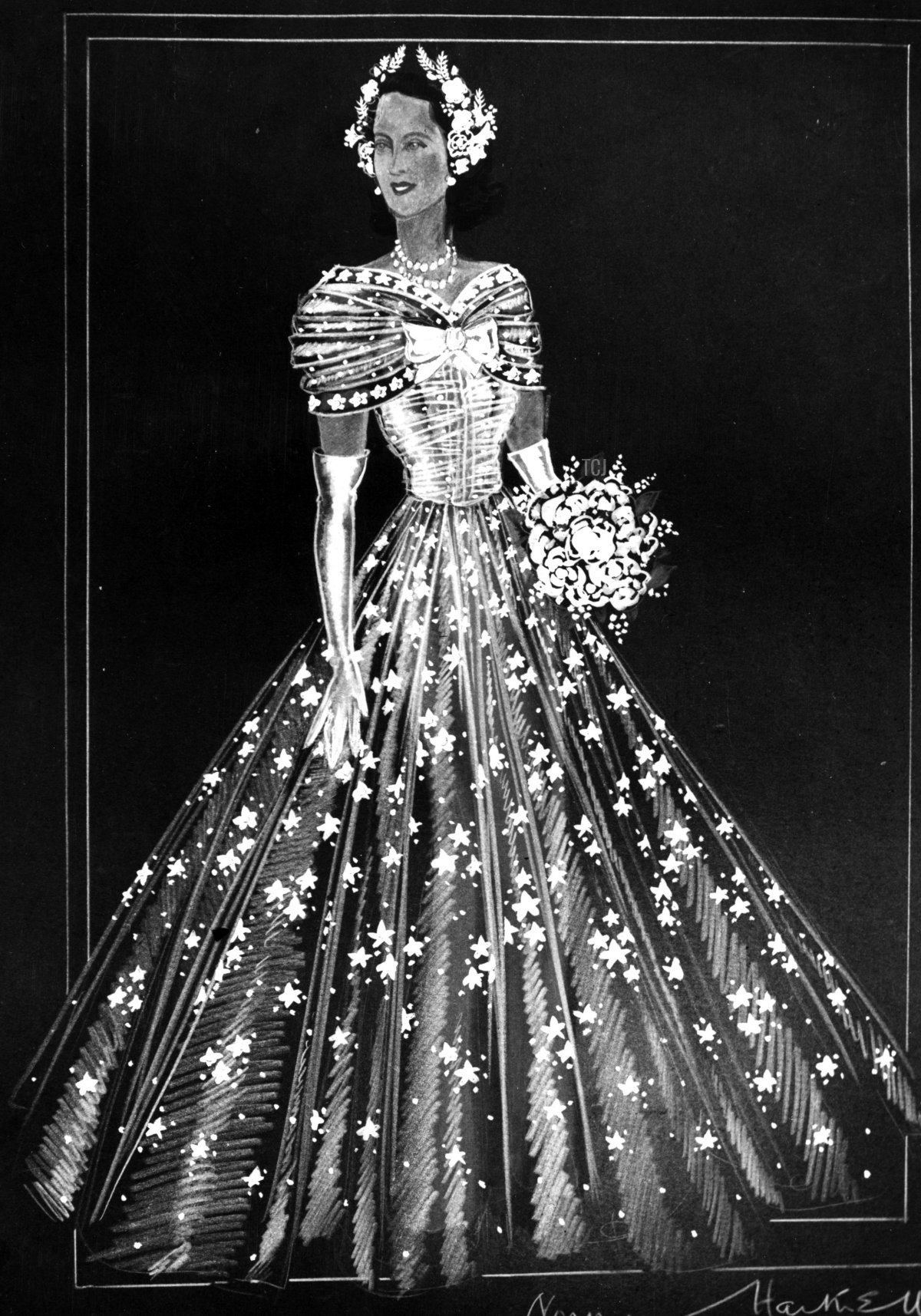

Shortly after ten, the bridesmaids arrived at the palace. The bridal party included eight relatives and friends: her sister, Princess Margaret; four cousins, Princess Alexandra of Kent, Margaret Elphinstone, Diana Bowes-Lyon, and Lady Mary Cambridge; two friends, Lady Elizabeth Lambart and Lady Caroline Montagu-Douglas-Scott; and one of Philip’s cousins, Lady Pamela Mountbatten. The girls were also clad in fabulous dresses by Hartnell, and they reportedly rushed to show Queen Elizabeth their gowns before heading to Princess Elizabeth’s private apartments. So far, the schedule had run like clockwork. But over the next hour, as the princess bride made her final preparations to leave the palace for the wedding ceremony, problems began to crop up.

With her makeup finished and her gown on, Princess Elizabeth was ready to add jewelry to her bridal ensemble. She borrowed a diamond fringe tiara from her mother for the occasion. The jewel, a legacy from Queen Mary, was set with diamonds that Mary had worn on her own wedding day in 1893. Queen Elizabeth wore the tiara often, including outings shortly before her daughter’s wedding day. But when the tiara was placed on the princess’s head that morning, it became clear that something wasn’t right: the frame of the piece had snapped in half.

Princess Elizabeth must have been filled with panic, but the presence of her mother and her friends must have helped to calm her. And even more calming would have been the nearby presence of the representative from Garrard, the crown jeweler, who was on hand to help in case of emergency. He hastily repaired the frame of the tiara, though the temporary fix left a small gap between two of the fringe sections that was visible in photos from the day.

But that wasn’t the end of the bejeweled drama for the morning. Princess Elizabeth had also planned to wear a pair of pearl necklaces for the ceremony, both of which had been given to her as wedding presents by her father. The Queen Anne and Queen Caroline Pearl Necklaces, as they’re generally called, are some of the oldest pearl necklaces in the royal vaults, belonging to Queen Anne (the last Stuart monarch) and Queen Caroline (the wife of King George II). Because they were part of the princess’s wedding gifts, the necklaces had been put on display with the rest of the presents at St. James’s Palace. But no one had remembered to retrieve them ahead of the wedding, and time was ticking before the bride had to meet her groom at the altar.

This time, a courtier stepped in to save the day. The Queen’s private secretary, Jock Colville, volunteered to run to St. James’s Palace to fetch the pearls. For those who have visited London, this may seem like it was a fairly simple errand—after all, St. James’s Palace isn’t very far from Buckingham Palace. But remember that the crowds had already gathered in the vicinity to see the bride on her wedding day, clogging the sidewalks, and police had cordoned off many of the streets to allow for the carriage processions to pass.

At first, Colville tried to make the journey by car. Conveniently, a limousine with diplomatic plates belonging to Elizabeth’s great-uncle, King Haakon VII of Norway, was easily accessible. Colville borrowed the use of the car, but the traffic restrictions meant that he couldn’t drive the full distance to retrieve the necklaces. Instead, he was forced to sprint for the remainder of the journey. He managed to secure the pearls and bring them back to the princess just in time for her to take a few bridal portraits before heading off for the church.

At 11:05 AM—just two minutes behind schedule—a coach carrying Queen Elizabeth and Princess Margaret set off from the palace for Westminster Abbey. Newspapers described the Queen’s dress as “a gown of apricot and gold lamé with tight-fitting sleeves, a pointed train and shoulder cape.” She also wore “a sable cape and an apricot and amber feather hat,” as well as the insignia of the Order of the Garter. Her jewels included Queen Alexandra’s Wedding Necklace and Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee Brooch. Several more coaches followed behind them, with one carrying King Haakon VII of Norway, Queen Friederike of the Hellenes (in a gold lamé gown and a feathered hat), and King Michael of Romania, and another carrying King Frederik IX and Queen Ingrid of Denmark (wearing a blue fox fur over a gray dress).

At the same time, Prince Philip departed from Kensington Palace in a car, accompanied by his best man and cousin, David, the Marquess of Milford Haven. Meanwhile, Queen Mary (wearing an aquamarine and gold chenille velvet gown with a cape and matching hat, plus pearls and diamonds, including the Cullinan III & IV Brooch) was traveling toward the Abbey from Marlborough House in a limousine procession. Also riding in cars in the same procession were Princess Juliana and Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands, Crown Prince Gustaf Adolf and Crown Princess Louise of Sweden, and the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester. Queen Mary’s procession arrived at the Abbey at 11:10, and Philip’s car pulled up outside the church five minutes later.

At precisely 11:16 AM, with drizzle falling, Princess Elizabeth and King George VI left Buckingham Palace in the Irish State Coach to travel to the Abbey. Bands played “God Save the King” as the carriage passed, and in a moment of excitement, members of the crowd broke through the police lines. Order was quickly restored, but the cheering reached a peak as the bride and her father passed by, waving to those who had gathered to wish them well. As they reached Westminster Abbey, another band began to play the national anthem. The King stepped out of the coach first and helped his daughter out of the conveyance. After a brief glance up at the famous façade of the Abbey, Elizabeth headed inside on her father’s arm.

The bridal procession assembled, with two small kilted pages joining the bridesmaids. The roles were filled by two of Elizabeth’s cousins: Prince William, six-year-old son of the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester, and Prince Michael, five-year-old son of the Duchess of Kent. Both boys stumbled a bit and struggled with the gown’s train as they walked down the aisle, but those were the only noticeable mishaps during the procession. The groom awaited his bride at the end of the aisle, along with the Dean of Westminster, the Archbishop of Canterbury, and the Archbishop of York.

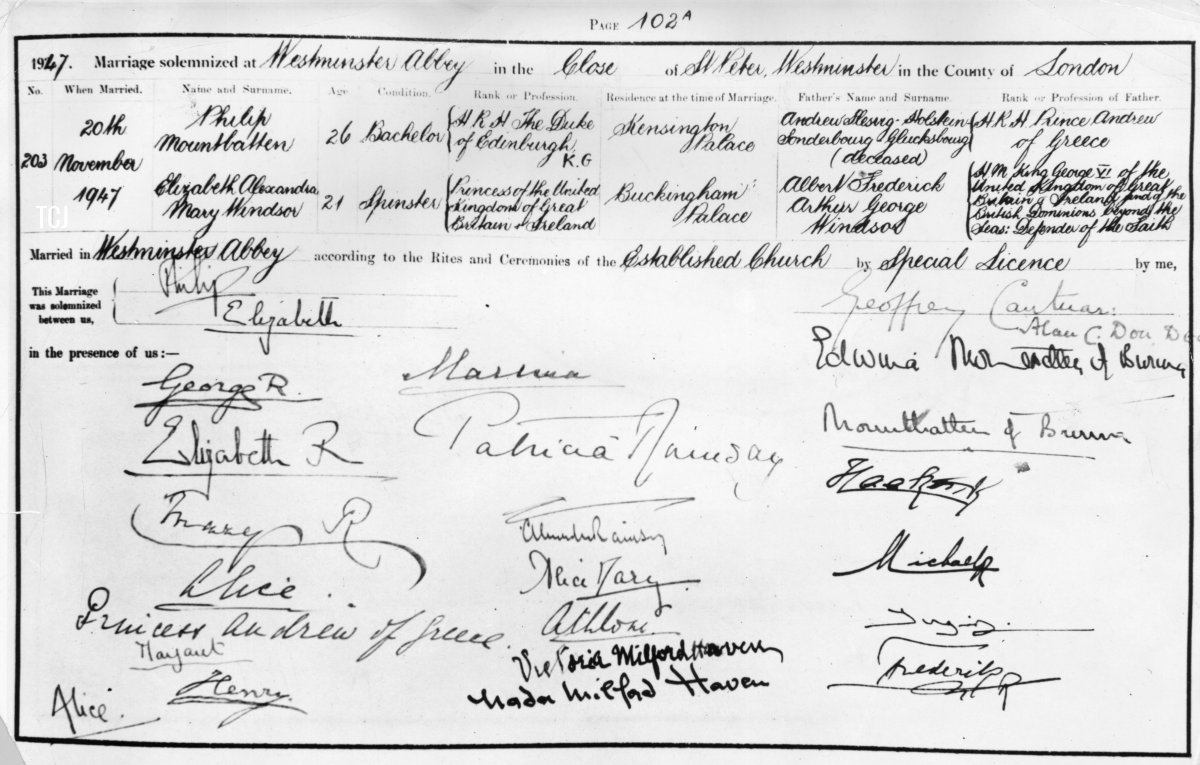

The wedding ceremony proceeded flawlessly in front of 2,000 invited guests. Reporters noted that Philip’s voice rang out clearly as he said his vows, while Elizabeth’s smaller and higher voice was sometimes more difficult to hear. Philip placed a wedding ring made of Welsh gold on Elizabeth’s finger, following royal tradition. As the couple moved to the chapel for the signing of the wedding registry, the King gallantly helped his two small nephews as they navigated the bride’s heavy train.

The wedding registry itself is a snapshot of the royal world at the time of the wedding. The first column features the signatures of Prince Philip, Princess Elizabeth, King George VI, Queen Elizabeth, Queen Mary, Princess Andrew of Greece and Denmark, Princess Margaret, and the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester. The second column includes the signatures of the Duchess of Kent, Sir Alexander and Lady Patricia Ramsay, the Earl and Countess of Athlone, the Dowager Marchioness of Milford Haven, and the Marchioness of Milford Haven. The third column of royal and family signatures features those of the Earl and Countess Mountbatten of Burma, King Haakon VII of Norway, King Michael of Romania, and King Frederik IX and Queen Ingrid of Denmark.

After bowing and curtseying to Elizabeth’s parents and grandmother, the couple processed down the aisle of the Abbey to the strains of Mendelssohn’s Wedding March. The royal pages were followed by the bridesmaids in an orderly column, with Lord Milford Haven walking behind.

As Elizabeth and Philip emerged from the Abbey, the sun tried valiantly to break through the November clouds. In her column for the International News Service, Inez Robb noted, “An old woman among the spectators outside the Abbey remembered the old adage and cried ‘Happy is the Bride the Sun Shines on’ when the pale orb showed itself through the murky sky.” She added, “No bride could have looked more radiant than the slim, petite girl who left the abbey clinging tightly to the hand of her bridegroom.”

Philip and Elizabeth rode in the Glass Coach for the procession back to Buckingham Palace, waving to the jubilant crowd all the way.

They posed for portraits inside the palace after their arrival, both as a couple and with their bridal party and families.

Here, the couple are posed with the bridal party (best man, bridesmaids, and pages), the bride’s parents, the groom’s mother, and their grandmothers.

Next was the wedding breakfast. The couple cut their wedding cake using the sword that Philip had worn with his uniform for the wedding, and their family, friends, and royal relatives toasted them with champagne. The couple and their family members also made two appearances on the balcony to acknowledge the cheering crowds outside the palace. The young Duke of Kent and Prince Richard of Gloucester (now the Duke of Gloucester) were allowed to join in this particular balcony salute.

At precisely 3:59 PM, Elizabeth and Philip left Buckingham Palace in a horse-drawn carriage to travel to Waterloo Station, where they would board the royal train to journey to Broadlands for the start of their honeymoon. The King and Queen were among the guests showering the couple with confetti as they departed. The rest, as they say, is history.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.