Seventy years ago this month, a future sovereign married a beautiful princess in a glamorous celebration that featured not one but two dazzling diamond wedding tiaras. But the royal wedding also came with a fair amount of drama, thanks to the complicated family of the princess bride.

The year was 1953. Six months earlier, in November 1952, the Belgian royal court had announced that Princess Joséphine-Charlotte, the sister of King Baudouin of the Belgians, was engaged to Prince Jean, the Hereditary Grand Duke of Luxembourg. The 32-year-old groom was the son and heir of Grand Duchess Charlotte of Luxembourg and her husband, Prince Felix of Bourbon-Parma. The 25-year-old bride was the daughter of the former King Leopold III of Belgium and the late Princess Astrid of Sweden.

Everyone wanted to know how the couple met and fell in love—if they were in love, anyway. A marriage between a prince and a princess was surely at least something of an arrangement, even if they had simply been told that they had to find a partner from within royal circles. Some press reports included vehement statements that the relationship was a love match, even calling the couple “childhood sweethearts,” while others whispered that it was simply a political union. In the documentary A Royal Family, however, Joséphine-Charlotte recalled telling her father that she was engaged. “To whom?” King Leopold exclaimed, suggesting that it may not have been a total arrangement after all.

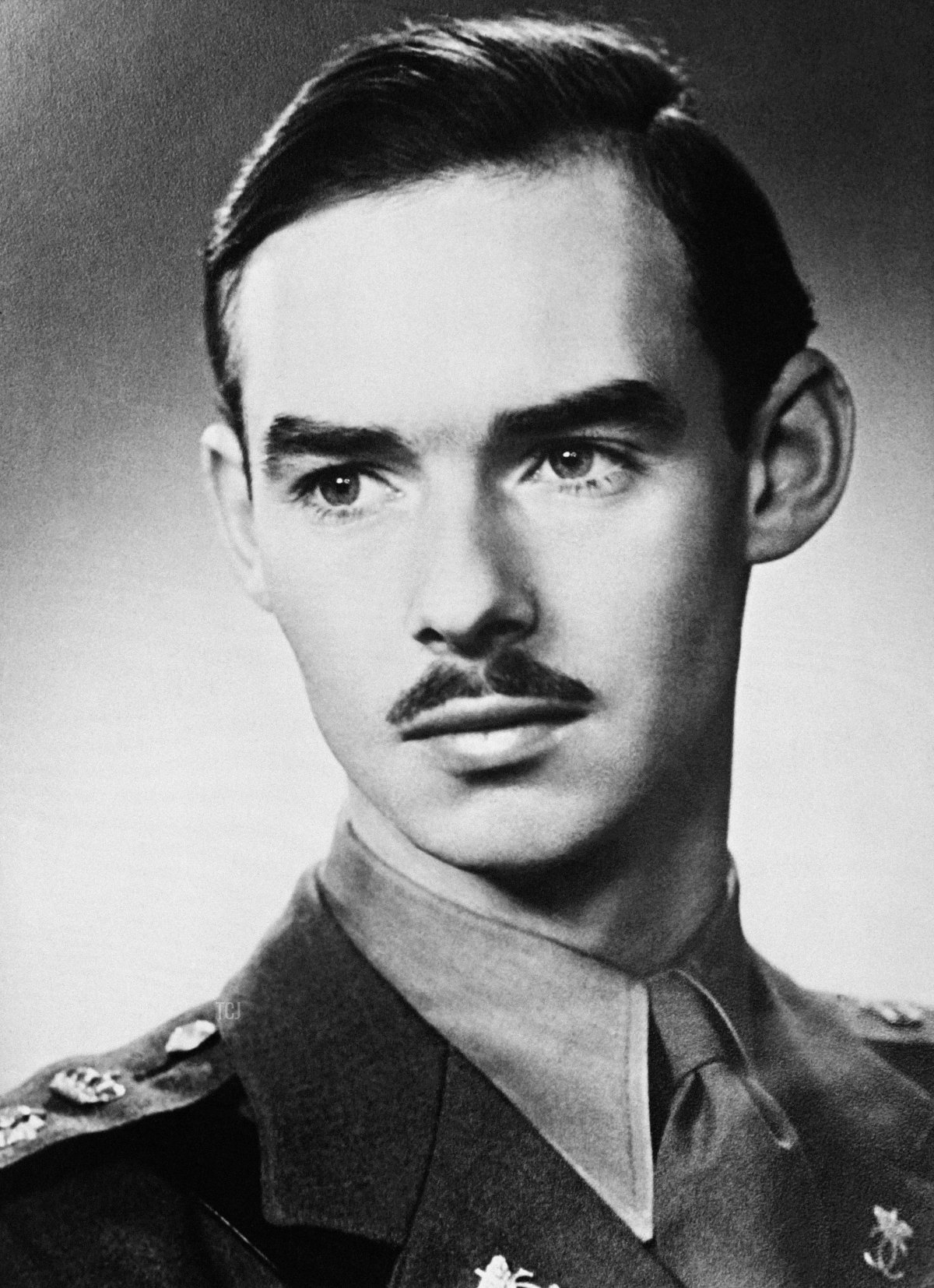

Prince Jean and Princess Joséphine-Charlotte were both members of the generation that endured World War II, and both had particularly tough experiences during the war years. Luxembourg was invaded by the Germans in May 1940, and Jean went into exile with his parents and siblings. After hopping around various European countries, the family sailed to America. But Jean decided to return to Europe to join the fight. He went to Britain, where he had attended boarding school, and joined the Irish Guards. By 1944, he was a captain, and that June, he participated in the invasion of Normandy. A few months later, he was also able to participate in the liberation of his own country.

Neighboring Belgium also suffered at the hands of the Germans during the war. For Princess Joséphine-Charlotte, though, the trauma of childhood had begun several years earlier. In 1935, when she was only seven, her mother, Queen Astrid of Belgium, was killed in an automobile accident. Five years later, the young princess and her brothers fled Belgium when the Germans invaded. Her father’s decision to capitulate to the enemy angered the Belgian people, many of whom saw him as a traitor. Leopold was placed under house arrest at the Royal Palace of Laeken, and his children returned to join him.

The king’s public reputation took another blow when, while in captivity, he decided to marry again. He wed a commoner, Lilian Baels, in a secret religious ceremony in the palace chapel. A civil wedding followed a few months later. While public opinion was decidedly mixed, Leopold’s children, including Princess Joséphine-Charlotte, grew to love their new stepmother and the half-siblings that were born after the wedding. Ultimately, though, Lilian never became queen consort, using the title of “Princesse de Réthy” instead.

In 1944, just after Prince Jean had landed on the shores of Normandy, the Germans deported Leopold, Lilian, and their children, imprisoning them first in Germany and then in Austria. Princess Joséphine-Charlotte remembered being so hungry that she resorted to eating dandelions. After the end of the war, the family still was unable to return to Belgium, because questions remained about Leopold’s actions and loyalty during the conflict. Ultimately, Leopold abdicated in favor of his eldest son, who became King Baudouin in 1951.

Princess Joséphine-Charlotte had lived and studied in Switzerland until 1949, when she returned to Belgium for the first time in five years. Around the same time, she made frequent trips to Luxembourg, visiting her godmother, Grand Duchess Charlotte, and the rest of the grand ducal family at Fischbach Castle. There, she was able to spend time getting to know Charlotte’s son Jean—the man who would eventually become Joséphine-Charlotte’s husband. After they announced their engagement, the prince and princess made numerous public appearances together, smiling and happy as they greeted the public.

But turmoil was apparently brewing ahead of the wedding day. Princess Joséphine-Charlotte’s unique royal family composition—morganatic stepmother, abdicated monarch father—didn’t fit easily into the strict order of precedence at the Luxembourgish court. And, because the wedding was being held in Luxembourg and not in Belgium, they were required to follow their rules. The matter of Lilian’s official title had not yet been settled, complicating matters significantly. The Telegraph reported that courtiers at the grand ducal palace in Luxembourg were “perturbed” by the whole thing.

The questions of precedence reportedly began to cause significant stress for the bride. Princess Lilian didn’t travel with her husband on an important pre-wedding trip to Luxembourg, and she wasn’t present at Laeken when Grand Duchess Charlotte and Prince Felix visited in March. Press reports stated that there was a possibility that Lilian would not attend the wedding at all. The Daily Telegraph reported on March 14 that “Princess Josephine Charlotte herself asked for [the] Princess de Rethy to be invited,” but “the difficulties of her precedence are believed to be insuperable.”

Not so, in the end. The pieces finally began to fall into place a few days before the wedding. In the official program, Lilian was referred to as “Princess Lilian of Belgium” for the very first time. In the bridal procession, Princess Lilian would be escorted by Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands. King Leopold would accompany his daughter to the altar, and King Baudouin, ceding the place of honor to his father, would walk with Queen Juliana of the Netherlands instead.

And then, just when plans were starting to fall into place, Queen Mary of the United Kingdom died on March 24, 1953. There were brief considerations of postponing the ceremony, but ultimately they decided to move forward. Princess Margaret, who was due to represent the British royal family at the ceremony, bowed out, replaced by G.C. Allchin, British minister to Luxembourg. Joséphine-Charlotte’s brother, King Baudouin, headed to London to represent the family at the funeral.

The wedding went forward as planned, but the bride still seemed weighed down by the entire experience. On the day before the wedding, she wept openly at the train station in Belgium before the family’s departure for Luxembourg, and reporters noted that she was “still looking pale” as the train crossed the border into her new country.

The princess’s dark mood didn’t improve as the wedding day dawned. On a rainy Thursday morning in Luxembourg, Jean and Joséphine-Charlotte were married in a pair of ceremonies. First came a civil ceremony at the palace, performed by Émile Hamilius, the Mayor of Luxembourg City. Reporters noted that the sun peeked through the clouds for a moment during the civil wedding, but the rain largely continued unabated, with the flags and festoons decorating the picturesque city soaked through. The Daily Telegraph‘s special correspondent observed that the processional route “was an avenue of umbrellas.”

Inside the cathedral, the bride’s demeanor was cause for concern among many guests. Reporters noted that, as Joséphine-Charlotte arrived on her father’s arm, she was “trembling and looked ready to faint,” adding that her “nervousness increased in the procession down the aisle at the end of the ceremony when guests scrambling to look at her stepped on her train, halting her three times.” The concern on Prince Jean’s face is plain in photographs from the wedding day. Twice during the ceremony he had to help her to her feet, and on one occasion, a priest had to step in to steady her. She appeared confused, taking up the wrong place at the altar and staying there throughout the ceremony.

So what was the problem? Gossip immediately began to spread among royal watchers that the princess was bereft because she was being forced into an arranged marriage. Officials quickly stepped in to squelch those rumors, and a variety of excuses were offered. The Telegraph correspondent blamed the “oppressive heat” of the lights set up by the film crew recording the ceremony. Perle Mesta, the colorful American ambassador to Luxembourg, told one columnist that Joséphine-Charlotte’s tears were caused by a pair of uncomfortable contact lenses. Another onlooker suggested that a continued struggle over precedence was an issue. The Daily Mirror reported that Prince Felix, the groom’s father, was offended when Princess Lilian almost violated the carefully-constructed order of the royal procession, rising too early from her seat after the ceremony and taking Queen Elisabeth’s place in line. (Newsreel footage shows that the procession went as planned, with Felix escorting Elisabeth as they left the cathedral.)

Luxembourg’s Foreign Minister Joseph Bech dismissed all of these rumors, offering a simple explanation that was probably largely accurate: the princess was suffering from both a physical illness and the sadness of leaving Belgium behind once again. Bech said that the princess “was suffering from a severe cold and from the heavy strain imposed on her by official receptions these last few weeks,” adding that “she was given medical attention after the wedding reception.” Joséphine-Charlotte’s hairdresser agreed, noting, that the bride “looked washed out before the wedding yesterday. She had a bad cold and was obviously feeling the strain of the farewells to her family and people.”

The bride may not have felt well, but she looked beautiful. Her wedding gown, made of white organza, lace, and taffeta, featured a fitted bodice with a high v-neck and an impressive four-yard train of Brussels lace. The bride also wore short lace gloves, a veil (which she kept over her face for the entirety of the religious ceremony and the journey back to the palace), and lots of diamonds, including a bandeau-style tiara and a simple diamond necklace.

This bridal tiara, though, is worth taking a minute to discuss. It’s a sleek and lovely diadem of diamonds, able to be worn both as a tiara and a necklace. Its history, though, is part of the legacy of colonialism on the part of the Belgian royal family. The tiara and its matching bracelet were made by Van Cleef & Arpels using Congolese diamonds, and the set was a wedding present from the colonial government of the Belgian Congo.

The now-Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Belgian royal family have a complicated and tragic historical relationship. While many colonies were claimed by countries, the Congo was personally owned by Leopold II of the Belgians himself. The history of the lucrative ivory and rubber trades and the atrocities that occurred as a result have had long-lasting consequences, to say the very least. In the summer of 2022, during his first visit to the DRC, King Philippe of the Belgians apologized for the actions of his ancestors, stating, “This regime was one of unequal relations, unjustifiable in itself, marked by paternalism, discrimination, and racism.”

The Belgian Congo gained its independence seven years after Jean and Joséphine-Charlotte’s wedding. The tiara has been worn by three more Belgian royal brides (Joséphine-Charlotte’s daughters, Princess Marie Astrid and Princess Margaretha, and her daughter-in-law, Grand Duchess Maria Teresa). But, maybe mindful of its colonial history, the family seems to have largely put it aside. They even planned to sell it in an auction of Joséphine-Charlotte’s jewels after her passing in 2005, but public outcry caused them to cancel the sale. (Many of the jewels, though, have been quietly and privately sold over the years since.)

Outside the heat of the packed cathedral, the rain-cooled air seemed to revive the new Hereditary Grand Duchess slightly. Reporters witnessed Jean quietly asking his bride if she felt able to participate in the procession back to the palace in an open car. She agreed, and newsreel footage captures her waving to the crowd as they drove through the streets of the grand duchy.

Back at the palace, the couple posed for their official wedding portraits. While some of the pictures feature the bride wearing the Congo tiara, she also changed into a second tiara for other pictures, including the portrait above. This second jewel is the Belgian Scroll Tiara. It was given to the princess by the Société Générale, a French bank, as a wedding present.

Made by Henry Coosemans, the diamond tiara is set in platinum. It may not have the kind of direct colonial ties that the Congo tiara does, but the diamonds in the scroll tiara were indeed also sourced from the Belgian Congo. The large 8.25-carat diamond in the center of the tiara can be removed and worn as a ring, and the entire central element can also be removed and worn as a brooch. Before the wedding, the tiara was displayed in the window of the jeweler’s shop in Brussels, and a long queue of onlookers filed past to see it in person.

While the bandeau-style Congo Diamond Necklace Tiara hasn’t been worn often in recent years, the Belgian Scroll Tiara remains one of the most-used royal jewels in the Luxembourgish collection. Like the necklace tiara, the scroll tiara was nearly sold after Joséphine-Charlotte’s death, but the family has retained it. It’s a particular favorite of Grand Duchess Maria Teresa, Joséphine-Charlotte’s daughter-in-law, who wears it often for state banquets and other galas.

You might think that a rainy wedding day and a downcast bride would have spelled trouble for Jean and Joséphine-Charlotte, but the couple had a particularly enduring and successful royal partnership. They had five children, including Henri, the current reigning Grand Duke of Luxembourg. Jean became Grand Duke when his mother abdicated in 1964, and he held the position until his own abdication in 2000. In 2005, two years after their golden wedding anniversary, Grand Duchess Joséphine-Charlotte died after a long battle with lung cancer. Grand Duke Jean lived to the remarkable age of 98, passing away in Luxembourg in April 2019.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.