Our journey through the sparkling lots of the upcoming Royal & Noble Jewels sale at Sotheby’s lands today with a gleaming gold, sapphire, and diamond brooch from Fabergé, given as a souvenir to remember a Romanov Grand Duke.

On November 13, auctioneers at Sotheby’s in Geneva will offer a unique grouping of bejeweled treasures connected to the former royal family of Bulgaria, as well as their relatives in Germany, Italy, France, and Russia. Lot #1113 in the sale, the jewel pictured above, is billed as an “imperial Fabergé diamond and sapphire brooch, St Petersburg or Moscow, circa 1909.”

The brooch is described in the lot notes of the sale as a “burnished gold knotted circle centering a bar collet-set with a cabochon sapphire, accented by old cushion-shaped diamonds, the reverse inscribed with Cyrillic initials V and A either side of an Imperial Crown for Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich, and the date 4 February 1909.”

The jewel does not apparently feature maker’s marks, but the experts at Sotheby’s are confident that it is the work of artisans from Fabergé, produced either in St. Petersburg or in Moscow. The brooch has twice been shown in recent jewelry exhibits in Stockholm and Munich, the latter of which was specifically an exhibition of Fabergé jewelry.

And here’s a model photograph from Sotheby’s that shows the scale of the piece. The brooch measures 3 centimeters across, or just a little over an inch.

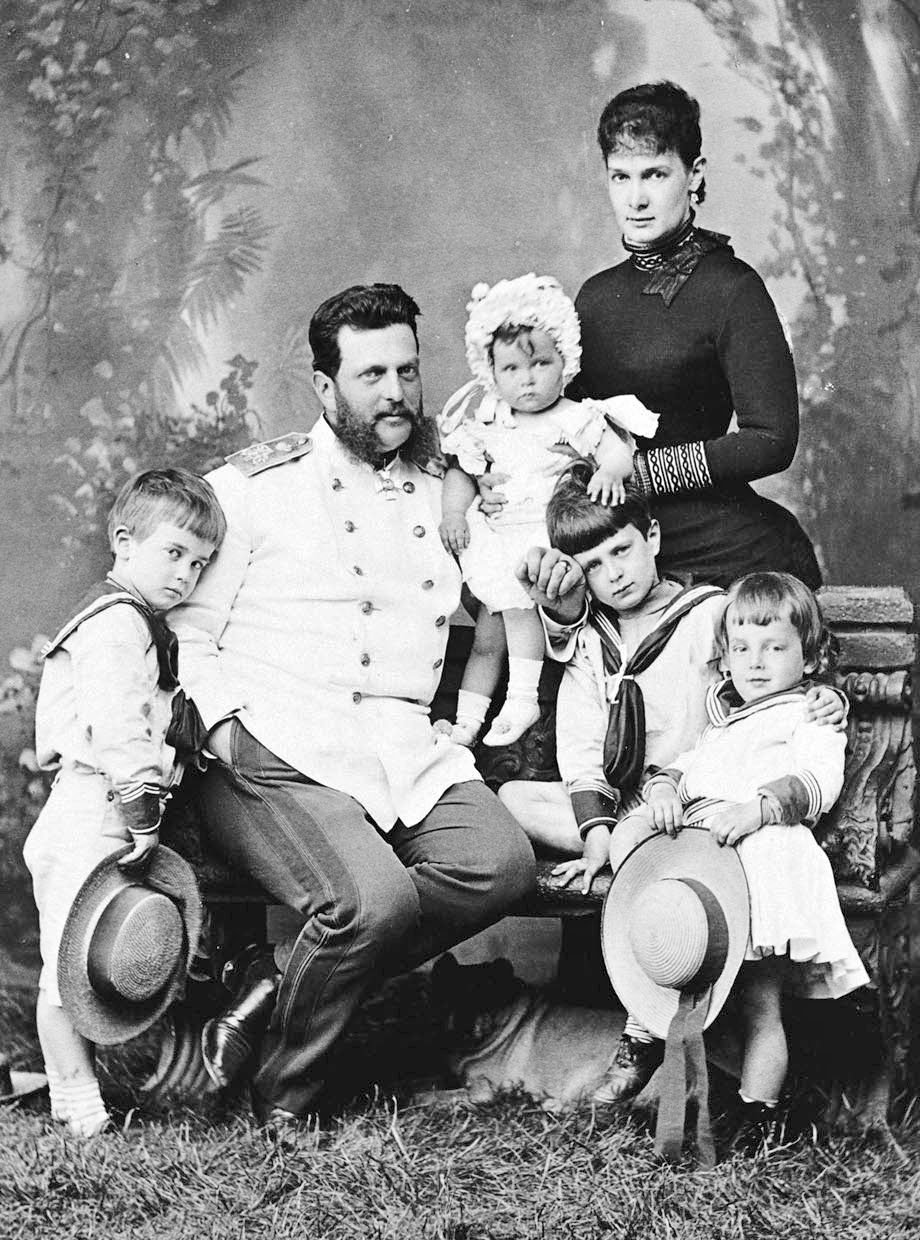

Sotheby’s notes that the brooch began its life as a different piece of jewelry: a button. It was apparently made for Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich, son of Emperor Alexander II, brother of Emperor Alexander III, and uncle of Emperor Nicholas II. Vladimir was, like his brother, a hulking figure who held numerous prominent military positions. But he was also reportedly artistic and intelligent, a voracious student and consumer of both books and gourmet meals.

In 1874, Vladimir married Duchess Marie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, a German princess who would become a gifted social hostess. Seventeen-year-old Marie was already engaged to someone else when she met 24-year-old Vladimir, but the two developed a genuine romance, and he convinced her to break off her engagement and marry him instead. She took the name “Maria Pavlovna” after their wedding. They had five children, four of whom survived to adulthood, raising them in the grand Vladimir Palace that he had built on the banks of the Neva. There, the devoted Vladimirs hosted gatherings so popular that they became seen as a rival to the imperial court of his brother and, later, of his nephew. The fact that there were sometimes conflicts between the couples helped to fuel that idea.

Grand Duke Vladimir’s later years were marked by conflict. He was the Military Governor of St. Petersburg in 1905 when the Imperial Guard opened fire on a group of unarmed protestors near the Winter Palace. Though he was not personally involved in the massacre, much of the blame was assigned to him. Later that same year, the Vladimirs found themselves at odds with Nicholas II when their son, Grand Duke Kirill, married Princess Victoria Melita of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Victoria Melita was the daughter of Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna, Vladimir’s sister and Nicholas’s aunt, making her Kirill’s first cousin–and marriages between first cousins were forbidden by the Orthodox Church. There was another emotional element at work, too: Victoria Melita had previously been married to and divorced from Empress Alexandra Feodorovna’s brother, Grand Duke Ernest Louis of Hesse.

Kirill and Victoria Melita were banned from Russia, and Vladimir angrily resigned from all of his military posts in protest. The rift with his nephew would not be fully resolved during Vladimir’s lifetime. The Grand Duke died suddenly in February 1909 of a brain hemorrhage at the age of 61. Maria Pavlovna was devastated and mourned him until her own death after the revolution.

So how did one of Grand Duke Vladimir’s buttons pop up in the collection of the former Bulgarian royal family? After the Grand Duke’s death, the Daily Telegraph wrote that Ferdinand of Bulgaria had received the news while traveling in Europe and had decided to go personally to Russia to pay his respects. The reporter noted that “Vladimir had been [Ferdinand’s] personal friend, had recently visited him at Sofia, had fought for Bulgaria’s independence thirty-two years ago, and was wedded to a relation of Prince Ferdinand’s present consort.” (Ferdinand’s second wife, Eleonore, was Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna’s first cousin. Both were granddaughters of Prince Heinrich LXIII Reuss of Köstritz.)

The Telegraph continues, “The impulse to pay in person the last tribute to the deceased Grand Duke must appear, under these circumstances, natural.” Why would anyone have suspected otherwise? Because Ferdinand had proclaimed Bulgaria’s full independence from the Ottoman Empire a few months earlier, announcing that the country was now a kingdom and giving himself the new title of Tsar. Traveling to St. Petersburg, and being treated as a king when he arrived, would have offered the appearance, at least, of Russian recognition of the new Bulgarian kingdom when the matter was still tenuous, especially where the Turks were concerned. Within the tense European political climate–the outbreak of World War I was only five years away–every diplomatic moment felt particularly weighted.

Ferdinand did go to the funeral. He telegraphed Maria Pavlovna directly, telling her that he deeply wished to be present at the funeral. His request was granted, and the Russian court took part in a careful reception with respect to Ferdinand’s status. The British Foreign Office weighed in, calling the Russian choice to treat Ferdinand like a king simply “an act of etiquette.” The Bulgarian ambassador in St. Petersburg hastily assembled a military uniform for Ferdinand to wear. But, reporters noted, it all seems to have worked. An imperial guard greeted Ferdinand as “Your Royal Majesty” on his arrival, and at the funeral, Ferdinand stood directly beside Nicholas II.

Ferdinand’s demeanor, the papers wrote, seemed like confirmation of his new status. “From the start to the finish Prince Ferdinand of Bulgaria was every inch a theatrical King,” the Telegraph wrote, noting that the “Bulgarian ‘Tsar’ was the most prominent figure in the most central position.” They added, “To the astonishment of the Diplomatic Corps Prince Ferdinand seemed transfigured, motionless, statuesque.”

At some point, Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna appears to have given Ferdinand one of her late husband’s gold buttons. She had the jewel engraved on the back with a crown and Vladimir’s initials, in Cyrillic text, as well as the date of his death, 4 Feb 1909 (per the Old Style dating system). Was the button a gift presented to him during the funeral trip? We don’t really seem to know for sure, but the engraving certainly tells us that it was meant as a memorial souvenir to remember the life and death of the Grand Duke.

Sotheby’s offers this comment on how the button-turned-memorial brooch arrived in Bulgaria: “Princess Nadejda of Bulgaria (1899-1958) received this jewel from Marie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Grand Duchess Vladimir (1854-1920) as a souvenir in 1909.” Princess Nadezhda, who was Ferdinand’s youngest daughter from his first marriage to Princess Marie Louise of Bourbon-Parma, would have been ten at the time. She doesn’t appear to have attended the funeral with her father, and I’ve not found reference to any other family member joining Ferdinand on the trip either. It’s possible, I suppose, that Maria Pavlovna gave the brooch to Ferdinand with the specific instruction to hand it to his daughter when he arrived back in Sofia.

The brooch will be sold in the November 13th auction at Sotheby’s in Geneva. Buyers looking to acquire a piece of Romanov history might be able to do so without spending an exorbitant amount. The current auction estimate for the piece is set at 5,500-7,000 Swiss francs, or approximately $6,300-8,000 USD.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.